The Soviet Plan to End the Weekend

There are seven days in a week. Monday through Friday, typically, are the work-week, at least in the United States. Similarly, in the U.S., Saturday and Sunday are the weekend. For many people, there’s a major difference during the work-week and the weekend — you go to work on the five days in the former group, but you don’t do so over the latter two. It should go without saying many, many people work over the weekend, of course, but that’s generally the exception. Turn back the clock a century and the weekend, and particularly Sunday, was even more commonly a day of rest.

And that was a problem for Josef Stalin.

When Stalin came to power in 1924, he did so with a desire to boost productivity at almost any cost — human suffering, in his eyes, being a perfectly acceptable side effect. By and large, the world had passed by Soviet Russia; Europe and the United States had gone through their Industrial Revolutions, producing things that Stalin could only dream of seeing made in the Soviet Union, and at speeds that seemed magical. Russia, on the other hand, was still an agrarian society, and one that had not yet benefitted yet from the technology being used in other parts of the world.

Stalin changed hat quickly, building factories across the landscape and requiring that men and women alike take on roles in these businesses. But the calendar was an institution that Stalin couldn’t change. Sunday, in particular, was a day of rest — most people in the nation took it as a Sabbath day, a religious day of rest, and even those who did not observe Christianity often spent time with family, friends, and their community. Saturdays, while not religiously significant for most, similarly was often a day off (although in many areas, a six-day workweek was the norm). And with none of the workers at the plant, the factories came to a halt.

Losing 15 to 25% of your week to a nationwide day off was something Stalin wanted to end, and in May of 1929, an economist named Yuri Larin proposed an idea. The idea, called nepreryvka, or a “continuous work week,” was very simple. The seven-day week would go away, being replaced by a five-day cycle. Each worker was assigned into one of five groups, basically at random. Each group would have one day off out of five. Except for the occasional state holiday, factories would never take a day off.

At first, Larin’s plan didn’t get a lot of attention from Soviet leadership, but when Stalin himself learned of the idea, he loved it — and put it into action almost immediately. By the end of June, Stalin announced the plan and established a commission to outline its details with two weeks. State-run media chimed in with approving coverage (imagine that) and by August, some factories had begun adopting nepreryvka on their own accord. The government made it official as summer gave way to fall, and on September 29, 1929, the Soviet Union held what could have been its final Sunday.

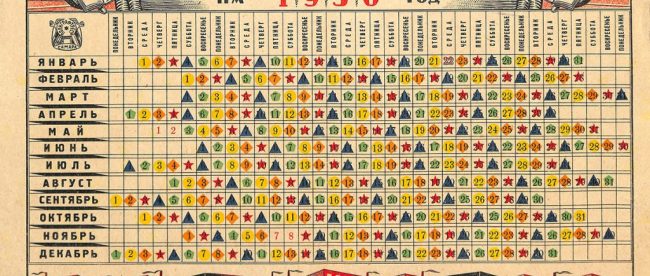

For the workers, the new system seemed like a small victory; as much of the country was, previously, expecting them to show up six out of every seven days, a four-out-of-five schedule seemed less taxing. After some initial confusion, the government issued calendars seen above (via here, larger version here), to make it clear when employees were to show up. But the transition wasn’t the hard part for the worker, as the disruption wasn’t simply to their internal clocks. Everyone’s entire way of life, at least outside of work, was turned upside down. Design publication Eye on Design summarizes the big complaints:

In just a year’s time, the strains of continuous shift work started to wear on the Soviet people who quickly realized that staggering rest days meant they rarely got to spend time with family and friends. A letter published in the communist newspaper Pravda on the day the nepreryvka took effect succinctly summed up the problem: “What is there for us to do at home if our wives are in the factory, our children at school, and nobody can visit us …? It is no holiday if you have to have it alone.” The nepreryvka appeared to also erase days of worship for most people since Sundays were now a work day for 80% of the population. The nepreryvka might have been designed as a tool for increasing productivity, but it was ultimately most successful at preventing people from organizing around anything other than labor.

For Stalin, though, these gripes weren’t a problem; if anything, they were a benefit. The History Channel noted that “Without a Friday, Saturday or Sunday, Muslims, Jews and Orthodox Christians alike would not be able to attend services, and that was considered a winning outcome, two years into the Soviet government’s campaign against religion. Innovations that might break the hold of religion on people’s minds, therefore, were met with enthusiasm [by Stalin and the Communist Party].” Similarly, again per the History Channel, “making family units less integrated may even have been a conscious part of the agenda. In the absence of technology.”

But nepreryvka just didn’t work. Families stayed together, despite the added hardship, and few workers gave up religious practices — instead, they were just less motivated at work. Productivity, despite the fact that factories never closed, actually suffered. To make matters worse, as the Atlantic reported, “officials worried that it affected attendance at workers’ meetings, which were essential for a Marxist education.” In 1931, with just a year of nepreryvka under its belt, the Soviet Union backtracked, re-instituting a universal day off once every six days. And by 1940, the country flipped back to the regular seven-day calendar we all know so well.

Bonus fact: The year 46 BCE was longer than most years — in Rome, at least. (As Wikipedia’s editors note, perhaps snarkily, “the actual planetary orbit-year remained the same”) In the year 45 BCE (that is, the year after 46 BCE), Rome was transitioning from the pre-Julian calendar to the Julian one, which required getting the pre-Julian calendar in sync with the sun and seasons. That required adding a lot of days to the calendar, and as a result, 46 BCE lasted 445 days.

From the Archives: When a Calendar Defeated Russia in the Olympics: Who knew telling that what day it is can be so difficult?