The Treasure of Bedford County

The solution, of course, is to bury the treasure, draw a map, and mark the treasure’s location with an “X.” History, folklore, and all sorts of modern children’s stories are replete with such things. Just run “treasure map” through a Google Image Search and you’ll find a seemingly infinite set of instructions telling you where to find endless amounts of buried gold.

No one believes any of those are real. But in one case, that hasn’t stopped people from trying. Welcome to the mystery of Thomas Beale’s gold.

Before we start, though, here are a few things to keep in mind: Thomas Beale’s gold may not exist, and may never have. For that matter, it’s not entirely clear if Thomas Beale himself ever existed. And even if he did, there’s a very good chance that someone more creative than him simply borrowed Beale’s name as part of a elaborate prank or sadistic wild goose chase. Because in 1885, someone purporting to be the recipient of Thomas Beale’s documents published the below.

As the story goes, Thomas Beale was a prospector of sorts who, with a team of two dozen or so others, struck gold somewhere within what is now known as Colorado in around 1819. For reasons inexplicable — most likely because the story is almost certainly fiction — no one could figure out how to decide how to divide up the loot. So they decided to entrust Beale to bring it to Buford County, Virginia, and bury it somewhere safe until they could resolve the issues. (Again, what?!) In order to make sure the other members of his party could find the treasure if need be, in 1822, Beale gave a lockbock containing series of three documents to an innkeeper in that area of Virginia named Robert Morriss. Beale instructed Morriss — who actually did exist — not to open the box until Beale or someone else from his team of prospectors returned for it, unless neither of those happened within ten years. Beale further informed Morriss that inside the box were encrypted instructions, which Morriss wouldn’t be able to decipher But, in ten years’ time, if Beale did not return, a colleague of his would mail the decryption key to Morris.

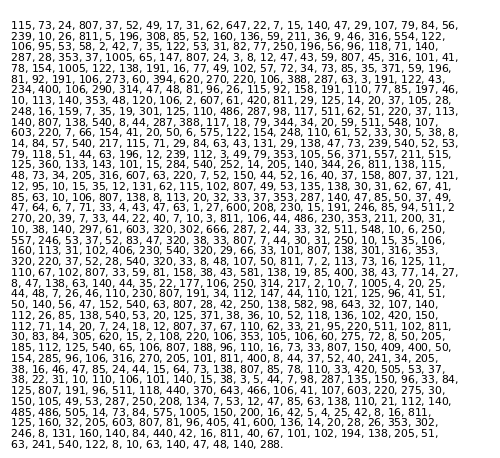

Beale never returned — ever. (That is probably because he most likely never existed.) No one else showed up either. So in or around 1832, Morriss opened the box and found three messages, each just a series of random-seeming numbers, one of which is reproduced below. And even in the land where this story is made up, that’s not anywhere near as useful as a map with a big red X on it, at least not without the key. But unfortunately for Morriss, Beale’s unnamed confidant never mailed the decryption key to the innkeeper. So Morriss just gave up, handing the papers over to friend. In time — again, per the story — the papers ended up in the hands of a man allegedly named James Ward by the year 1885. Ward’s company published the pamphlet pictured above, including the cipher below.

But Ward went one step further. Somewhere along the line, someone figured out that the decryption key for the second cipher (the one above) was the Declaration of Independence. Each number corresponded to a word in that famous document and, if you took the first letter of that word, you’d start to spell out a message. Deciphered, the message reads as follows (thanks, Wikipedia!):

I have deposited in the county of Bedford, about four miles from Buford’s, in an excavation or vault, six feet below the surface of the ground, the following articles, belonging jointly to the parties whose names are given in number three, herewith:

The first deposit consisted of ten hundred and fourteen pounds of gold, and thirty-eight hundred and twelve pounds of silver, deposited Nov. eighteen nineteen. The second was made Dec. eighteen twenty-one, and consisted of nineteen hundred and seven pounds of gold, and twelve hundred and eighty-eight of silver; also jewels, obtained in St. Louis in exchange for silver to save transportation, and valued at thirteen thousand dollars.

The above is securely packed in iron pots, with iron covers. The vault is roughly lined with stone, and the vessels rest on solid stone, and are covered with others. Paper number one describes the exact locality of the vault, so that no difficulty will be had in finding it.

So Ward included that in his publication. In a perfect world, the next sentence you’d read today is something like “but no one was foolish enough to throw fifty cents — about $13 in today’s dollars — after an obvious ruse.” But you know better than that. According to the book “The Code Book: The Secret History of Codes and Code-breaking” published in 1990, the region sees its share of treasure hunters each summer, even a century later. (Some bring psychics to help. Of course.)

To date, no one has found the treasure, and the two ciphers remain unsolved. And, for good measure, Thomas Beale still hasn’t returned to Robert Morriss’ inn.

Bonus fact: Virginia (although not Bedford County, Virginia) is home to a styrofoam version of Stonehenge known as “Foamhenge.” No treasure is buried there. There’s also a “Carhenge” in Nebraska, made of American-made cars spray painted silverish-gray. No treasure is buried there, either.

From the Archives: Münchausen by Internet: The greatest trick the Internet ever told?

Related: A reproduction of the Beale papers, for about $12, published in 2009 … by something called the Dodo Press. Some things, you just can’t make up. More seriously, “The Code Book” was a very well received book, with 338 reviews averaging 4.7 stars on Amazon.