Unreal Money

Brazilian currency is called the real, which is the Portuguese word for the homographic English word “real.” Brazilian reals have been in circulation since July 1, 1994. But they were also in use from March 1994 until then — kind of. For those three months, the real was anything but real. It was, rather, pretend — entirely non-existent. The hope was that by creating a monetary system which did not have any currency representing it, they could save the Brazilian economy.

And by most measures, it worked.

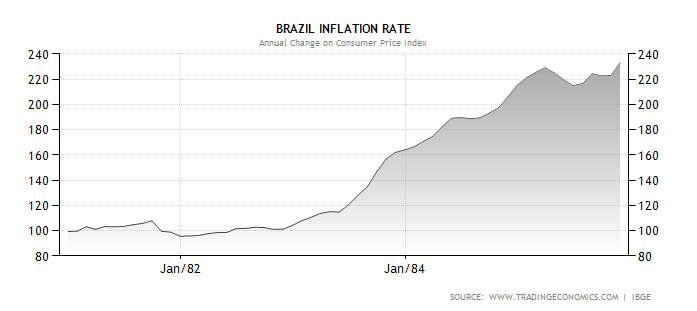

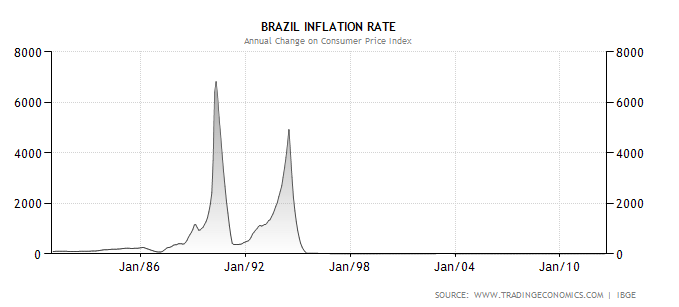

Inflation was running rampant in Brazil in the early 1980s, climbing with no end in sight through the beginning of the decade, as seen by the first graph below. And then, things went from horrible to unimaginable — it spiked to over 6,000% (annualized) in January of 1990, as seen in the second graph, dwarfing the problems of the decade prior. The rate of increase slowed down soon after but was still very high, until July of 1994, when it spiked again. But after that spike, it quickly leveled off, and within a year, inflation was down to rates one would see in a typical, generally economically healthy country.

The rampant inflation, in part, was caused by an economic term of art called “inflationary expectations.” NPR’s Planet Money explains how quickly things were going downhill, and why:

[In 1992], Brazil’s inflation rate hit 80 percent per month. At that rate, if eggs cost $1 one day, they’ll cost $2 a month later. If it keeps up for a year, they’ll cost $1,000. In practice, this meant stores had to change their prices every day. The guy in the grocery store would walk the aisles putting new price stickers on the food. Shoppers would run ahead of him, so they could buy their food at the previous day’s price.

In March of 1994, Brazil’s inflation rate was nearly 45% a month. With consumers now expecting prices to increase on a day-to-day basis, inflation became a beast unto itself. To stop this, the government decided to try and reprogram consumers’ brains into thinking that price were, somehow, stable. The currency of the time, called the cruzeiro real, was rapidly losing value, so they introduced a new one called the unidade real de valor, or URV, which translated to “real value unit.” Wages and taxes were stated in terms of URV. As the Los Angeles Times reported, wholesalers and retailers were advised to display each products’ price in URV. They were further asked to keep products’ URV price relatively constant. What changed, instead, was the amount of cruzeiro real each URV was worth. All transactions, from buying milk to paying one’s taxes, were conducted using cruzeiro real, not URV.

Why? Because the URV never existed, at least not in currency form. Edmar Bacha, an economist who helped come up with the URV concept, told NPR that the URV was “virtual — it didn’t exist in fact.” No bills, no coins, nothing. URV was a non-currency reference point aimed at demonstrating some sort of price stability to a population which no longer believed such things were possible.

About three months after the URV system was implemtened, it and the cruzeiro real were replaced. On July 1, 1994, Brazil announced a new currency — the real now used by Brazil, with the real’s value pegged to one URV. As seen by second graph above, the rapid rise in inflation abated soon after, and Brazil’s economy recovered.

Bonus fact: In 2006, Gregor Smith, a professor of Economics at Queens University in Ontario, Canada, published a working paper plotting Japan’s employment rate (negative) on the X-axis and its inflation rate on the Y-axis. His findings? The graph looks like Japan (3 page pdf).

From the Archives: The Aptly-Named Snake Island: An island off the coast of Brazil that, true to its name, has a lot of venomous snakes.

Related: “All Meat Looks Like South America” by Bruce McCall. The book is cited in Professor Smith’s paper on Japan and features a picture of Brazil (and corresponding lookalike meat) on its cover.

Charts via Trading Economics

Leave a comment