We Use to Recycle Penicillin from Patients’ Urine

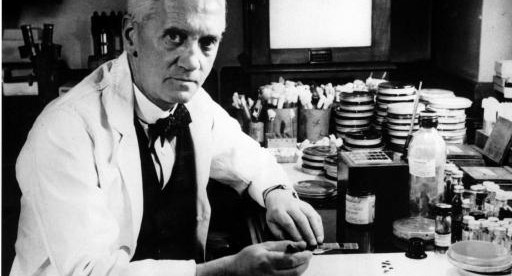

Penicillin was discovered by a scientist named Alexander Fleming in September of 1928. Two years later, it was used for the first time to cure an infection — on November 25, 1930, British doctor Cecil George Paine used penicillin to help an infant suffering from neonatal conjunctivitis. By the end of 1944, penicillin was being produced in high enough quantities to change the fate of those wounded in World War II. As PBS NewsHour explains, “throughout history, the major killer in wars had been infection rather than battle injuries. In World War I [which ended a decade before Fleming’s discovery], the death rate from bacterial pneumonia was 18 percent; in World War II, it fell, to less than 1 percent.”

Making such an advancement took a lot of penicillin — but the capacity to create the drug wasn’t adequate to meet the need. (And the fact that most manufacturing facilities were dedicated to the “killing people” part of the wartime effort didn’t make it any easier.) But there was good news: penicillin could be reused. That is, if you gave a dose to a patient, it didn’t just disappear into the body. Most of it just went straight through, coming out in a reclaimable, still-useful form.

You just had to harvest the patient’s urine first.

Discover Magazine’s aptly-named “Body Horrors” blog explains:

After one administration of injected penicillin, anywhere from 40 to 99 percent of the antibiotic is excreted in urine in its fully functional form about 4 hours after administration thanks to our efficient and hardworking kidneys. Due to this distinct feature of its pharmacokinetics, penicillin could be extracted from the crystalized urine of a treated patient and then used to treat another patient in the throes of serious bacterial infection just next door. In 1943, just shy of one year after its successful usage in saving the aforementioned woman’s life, the total amount of penicillin that had been produced was enough to treat only a hundred people, and this only if it was judiciously reclaimed and reused. Recycling penicillin wasn’t just smart; it was a necessity for such limited quantities of this wonder drug.

The downside of all this penicillin passing through patients was that it wasn’t in the body long enough to be effective, so doses had to be re-administered until the infection was under control. Over time, medical science found a way to slow down penicillin’s path through our bodies and increase absorption, and as a result, less of it came out the other side. At around the same time, our collective ability to produce more and more of the antibiotic made recycling a patient’s urine unnecessary.

Thankfully.

Bonus Fact: According to Defeat Diabetes, a diabetes awareness organization, a similar (and arguably even more disgusting) principle was used by diagnosticians in about a millennium ago to detect that disease. “Since the urine of people with diabetes is thought to be sweet tasting,” the organization explains “diagnosis [was] often made by ‘water tasters’ who [would] drink the urine of those suspected of having diabetes.” Overly sweet urine suggested that the patient had the illness.

Bonus Fact: According to Defeat Diabetes, a diabetes awareness organization, a similar (and arguably even more disgusting) principle was used by diagnosticians in about a millennium ago to detect that disease. “Since the urine of people with diabetes is thought to be sweet tasting,” the organization explains “diagnosis [was] often made by ‘water tasters’ who [would] drink the urine of those suspected of having diabetes.” Overly sweet urine suggested that the patient had the illness.

From the Archives: Keeping the P in Space: Another example recycling urine.

Take the Quiz: Name the Words Containing the Consecutive Letters “Pee.”

Related: “The Life of Pee: The Story of How Urine Got Everywhere” by Sally Magnusson. I have no idea the book is any good but the description sounds pretty interesting if not gross.