Why You Shouldn’t Always Read Between the Lines

Great works of art are analyzed and overanalyzed, as fans and scholars alike look for hidden meaning in symbolism. Off the top of your head, you can probably come up with a half-dozen examples yourself, and some of them are probably right. Take, for example, “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” the novel, written in 1900, upon which the movie “The Wizard of Oz” is based. Is it a story about a girl who falls asleep and has a very vivid, weird dream? Or is it actually a critique of turn-of-the-century monetary policy? An anti-Native American screed? A veiled rant against technology? All of these have been floated and debated over the last century, as cataloged here by Wikipedia.

For high school and college students, the idea that an author’s writing may have a deeper meaning has given root to thousands of homework assignments. Teachers instruct students to read a book and then write a report explaining why such-and-such symbolizes so-and-so and why. In later years of education, students may even be asked to support their conclusions by placing the novel into a historical context. It’s a tried-and-true way to test a student’s reading comprehension and critical thinking.

But in 1963, a high school student named Bruce McAllister decided he didn’t want to guess; as Mental Floss explains, “he was sick of symbol-hunting in English class.” So he went straight to the source and asked the authors themselves.

McAllister’s efforts were impressive. In a world where emails, printers, and even fax machines were a total fiction, McAllister still managed to reach out to the living legends whose work he read in class. As Brain Pickings describes, the teenager “devised a four-question mimeographed survey to probe the issue and mailed it to 150 of the era’s most notable writers.” His efforts did not go unnoticed — 75 of those he wrote to wrote back.

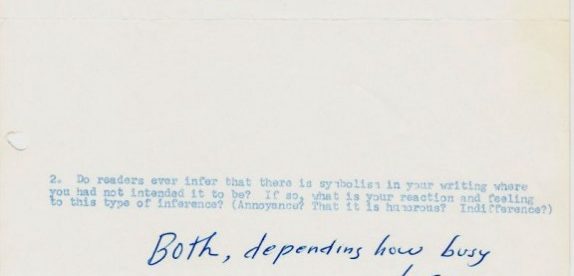

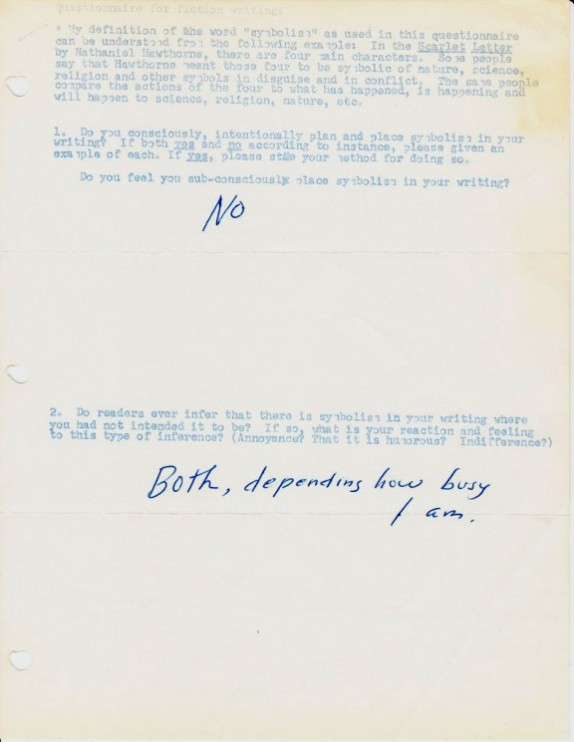

Some offered only pithy replies; to McAllister’s question as to whether the author felt that he or she “subconsciously placed symbolism” in their writing, Jack Kerouac, for example, replied with only one word: “No,” as seen below. (And be sure to read the other question and answer presented.)

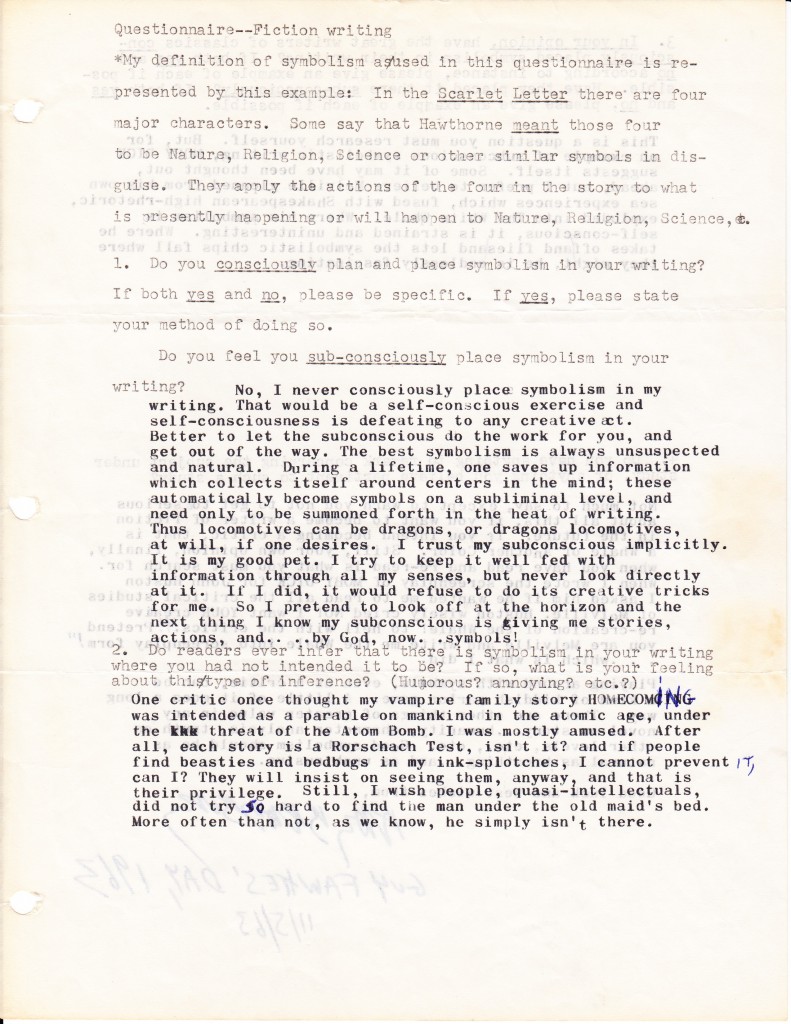

Others were admonishing; Ayn Rand took issue with McAllister’s definition of “symbolism,” writing “this is not a ‘definition,’ it is not true — and, therefore, your questions do not make sense.” But some were supportive and thorough. Take, for example, the reply of Ray Bradbury:

In 2011, the Paris Review caught up with McAllister — by then a successful author in his own right — to review his results. Unfortunately, there was no common theme across the replies; some writers intentionally layered in symbolism, some did so unintentionally, and some weren’t all that cooperative with the survey’s hopes. But McAllister did draw one lesson from the experiment: “The conclusion I came to was that nobody had asked them. New Criticism was about the scholars and the text; writers were cut out of the equation. Scholars would talk about symbolism in writing, but no one had asked the writers.”

More results from McAllister’s survey can be found at the Paris Review’s website, here.

Bonus fact: Jack Kerouac’s most famous novel is “On the Road,” and if you read it as originally written, it is kind of like being on a road. That’s because Kerouac’s original manuscript isn’t written in a notebook or in a binder or anything else with pages. It’s written on a scroll, as seen here. The 120-foot long scroll is made up of sheets of tracing paper that Kerouac cut up and taped back together, and while typed, it contains no margins or paragraph breaks. It’s also worth a small fortune — in 2001, Jim Irsay (who also owns the much-more-valuable Indianapolis Colts) purchased the scroll for $2.43 million.

From the Archives: Road Rage: The weird hobby of someone who definitely thinks there’s a lot of symbolism in Ray Bradbury’s work (and that of many others, too).