The Poison Squad

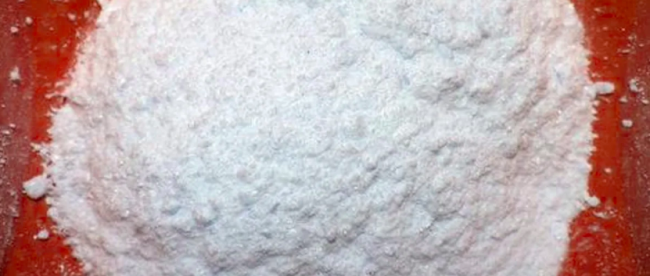

Pictured below is a powered version of an organic compound. Wikipedia describes it as “white, consisting of soft colorless crystals that dissolve in water.” It’s not flammable and is odorless. You can buy it at the local drugstore without a prescription; you can probably find it at your local grocery store, too. There’s a pretty good chance you have it in your home already.

But: is it safe to eat?

Given the above information and, for that matter, the picture, there’s really no way to tell, right? It could be sugar, which is safe (although probably not great for you, especially if you eat a lot of it). But it’s not. That’s borax, and specifically, borax-based laundry detergent. You don’t want to eat it because doing so can be dangerous. Per Healthline, consuming too much borax can cause skin irritation, vomiting, respiratory issues, and other symptoms commonly associated with poisoning. In the United States and in many other places around the world, borax can’t legally be used as a food additive.

But that wasn’t always true. A century ago, borax was a common food additive — as was anything else that could lengthen shelf life, cut costs, or improve the taste. As Eater explains, “at the turn of the 20th century, American food producers could get away with putting just about anything in their food. And they did. Milk was full of chalk and formaldehyde. Canned food had salicylic acid, borax, and copper sulfate. Producers sold corn syrup as honey and colored lard as butter, and there were no laws or consequences to false labeling.”

As we all know now, that’s changed. But to get there, we needed to do something crazy by today’s standards: we tried to poison ourselves. Intentionally. Okay, not all of us. Just a small group in Washington, colloquially called “The Poison Squad.”

In 1902, Dr. Harvey Washington Wiley, the chief chemist at the United States Department of Agriculture, was concerned that a lot of these additives were harmful — but few people in power cared. Dr. Wiley aimed to change that, and it required a two-pronged approach: first, he had to demonstrate that certain additives actually were harmful (and at what amounts), and second, he had to do so in a way that couldn’t be easily ignored. Slate summarizes Wiley’s efforts:

His plan was simple from the beginning. He’d build a test kitchen and dining room in the basement of the Agriculture Department building on Independence Avenue. Then he’d serve poisoned food to a group of young volunteers. Wiley chose men in their 20s because he thought they were sturdy enough to withstand the diet he had in mind.

The first 12 members of the squad were all department employees who had agreed to eat their meals in Wiley’s kitchen over a span of six months. The menus were set so that each day’s food would include exactly one suspect ingredient. Squad members never knew what possible poison they were eating. Still, they all signed waivers absolving the government of liability for possible health impacts.

Wiley and team monitored every aspect of the volunteers’ health and wellness over the course of these culinary rollercoasters. According to Esquire, “before each meal, they had to weigh themselves, take their temperatures and check their pulse rates. Their stools, urine, hair and sweat were collected, and they had to submit to weekly physicals. When one member got a haircut without permission, he was allegedly sent back to the barber with orders to collect his shorn locks.” It was critical that Wiley control as many outside factors as possible — the food industry was lobbying hard to keep any Wiley-driven reforms from ever becoming law. Wiley didn’t even pay the volunteers (other than giving them free, but probably tainted meals), likely to keep at bay accusations of bias. As participants fell ill — sometimes very ill, although thankfully, there were no deaths — the press took notice.

Wiley’s efforts captured the attention of the nation and skepticism over food additives and the accuracy of labeling came into the spotlight. Washington began to act, and in 1906, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, the precursor to our current food laws and regulations.

Bonus fact: One person Dr. Wiley didn’t have to convince was Henry J. Heinz, founder of the ketchup and condiment company that bears his name. Heinz got his start in horseradish and knew that his competitors often put a lot of unsafe additives into their product. Heinz didn’t want to do that, and he wanted consumers to give him credit for his honesty. As a result, according to Fast Company, “when Heinz began his career selling horseradish, he refused to sell it in the brown opaque bottles common at the time. Instead, he used transparent jars, so that buyers could see his horseradish’s purity for themselves before they gave him a penny.”

From the Archives: Why You Shouldn’t Eat Those “Do Not Eat” Packets: They’re not poison. But they are dangerous.