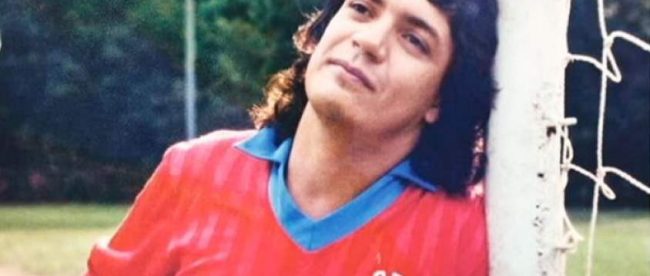

The Greatest Soccer Player Who Never Was

Carlos Henrique Raposo, pictured above, was born a day late in 1963. Not medically-speaking — his due date remains unreported — but karmically. Raposo — who went by the name “Carlos Kaiser” — was born on April 2nd of that year, one day after April Fool’s Day. It’s too bad, too, because he was a master at playing others for fools.

Kaiser was born a soccer fan — growing up in Brazil in the 1960s and 1970s, one almost had to be. Like many of his classmates, Kaiser played youth soccer as both an adolescent and then as a teen. Unlike most of his friends, though, Kaiser’s play caught the eye of a professional club team. In 1979 — still just sixteen years old — the young man became the newest member of Puebla. This was his ticket out; he’d later tell Brazilian media giant Globo (via and translated by Atlas Obscura) that “like every other soccer player, I came from a poor family, but I want to be big, have a lot of money so I could give better life conditions to my family.” Unfortunately for Kaiser, things didn’t work out immediately — Puebla released him before he ever got into a game. While Kaiser was a physically gifted young man, he wasn’t a very good soccer player — those skills never developed. The dream should have ended there, as getting cut at that point is often a career-ender.

Kaiser, undeterred, decided to go on a different career path: a soccer-playing con-artist, one who hid his pedestrian ability by never actually playing.

At the time — and this is still somewhat true today — marginal soccer players can find limited work on short-term contracts, sometimes weeks or months long. Kaiser quickly found that whatever coaches thought a fill-in soccer player should look like, well, Kaiser looked the part. Some of his friends — legit soccer players — would attest to his physical abilities and just leave out the part about his lack of soccer know-how (or just pass him off, euphemistically, as “raw” or “untapped”), giving him a leg-up on the competition. One team after another would sign Kaiser to a contract for a few months.

A guaranteed paycheck as a soccer player in-hand, Kaiser would kick phase two of his plan into action. First, he’d say he needed a month or so to get back into peak physical shape — the brief interval between soccer gigs had a net negative impact on his strength, stamina, and the like. After that, he would join the team for practices — and then fall shortly after he got onto the pitch, falsely claiming to have pulled a hamstring. (If that didn’t work, he had a dentist at the ready to lie about an infection.) Without an MRI or other modern techniques readily available to diagnose the injury, the team would simply keep Kaiser on the bench until his contract ran out.

But that’s not what the local press would report. Kaiser would take advantage of his access to free team gear; he’d use it to bribe local reporters to write fawning reviews of his soccer prowess. So when Kaiser finally “healed” and was in search of a new team, it was an easier case to make: in the pre-Internet era, it was virtually impossible to contract these on-the-record accounts of Kaiser’s achievements, and unsurprisingly, Kaiser had little trouble getting a new contract with another team. From 1979 and into the 1990s, Kaiser signed contracts with as many as ten different soccer teams.

But he never played in a game.

There was a close call, though. In the late 1980s, Kaiser signed with Bangu, a club that plays its home games in Rio De Janeiro. At the time, one of its owners was a man named Castor de Andrade, who made his fortune as a banker who operated an illegal gambling game in the area — and who likely engaged in a lot of violent criminal activity to protect those interests. Castor was a big fan of Kaiser (or the legend of Kaiser, at least) and was getting increasingly frustrated that the star player wasn’t playing.

Castor forced the issue. During one match, with Bangu down 2-0 early, Castor sent a message to the coach (via walkie-talkie) that Kaiser was to be put into the game. Kaiser acted quickly. He spotted an opposing fan in the stands who was heckling the team and, per the Guardian, “used it as an excuse to start a brawl with the away supporters.” The referees immediately threw Kaiser out of the game — before he had even gotten onto the pitch.

Kaiser wasn’t thrown off the team for his errant behavior, though. He told Castor that the fan had accused him of being a thief; Kaiser was just defending his honor. Castor, still enamored with the soccer star in his midst, not only forgave Kaiser — he also gave him a six-month contract extension.

Bonus fact: In most of the world, it’s called “football”. In the U.S. and Canada, it’s called “soccer”. How do two very different words come to mean the same thing? The sport (whatever term you prefer, it’s the same sport) is more formally known as “association soccer,” a name coined to differentiate the game from rugby football. The latter’s name shortened over time to simply “rugby” and in most of the world, the word “association” simply faded away from the former. But in some areas, “association” also shortened — to “soccer.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “soccer” split off as its own, stand-alone term in 1863.

From the Archives: Why Pelé Tied His Shoes Before a 1970 World Cup Match: And not because they were untied.