A Back-Alley Way To Create a Successful Board Game

Sierra Leone is a small nation on the west coast of Africa. (Here’s a map.) A total of eight million people live in the nation, with one million of them residing in the capital city of Freetown. No other city has even a quarter-million people in it, making most of the population rather spread out. And unfortunately, driving there can be treacherous. Before 2013, it was legal to drive a right-hand vehicle in Sierra Leone, despite the fact that two-thirds of accidents in the nation involved such vehicles. Banning right-hand vehicles helped, but there was more reform needed. The adult literacy rate in the nation is under 50%, making it hard to teach the rules of the road. Books weren’t an option, videos were often boring, and in-person learning wasn’t feasible at scale.

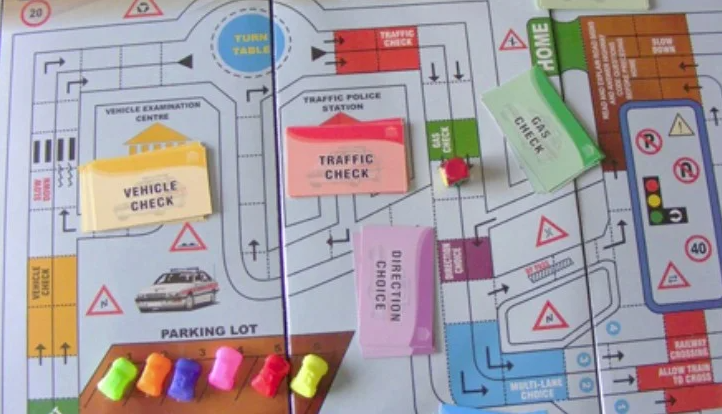

The solution? You can see it below.

For years, Morie Lenghor, the Assistant Inspector General of the police, was subjected to one gruesome accident after another. And a lot of them were, in his view, preventable: he told Reuters, “most crashes here are a result of ignorance of the highway code. And most drivers don’t even understand half the road signs.” And he attributed that to the nation’s low literacy rate: “I realized that a lot of people don’t like reading much, but what if I can put the highway code in a game that is attractive to young people?”

So he created a board game. Pictured above is “The Driver’s Way,” the game in question. According to Auto Evolution, the game “is similar to Monopoly [which is a terrible board game, by the way], the players having to move pieces modeled like classic cars around a colorful board after rolling dice to advance.” But you don’t buy properties or houses; as Auto Evolution notes, “to advance, the players must know real-life traffic rules.” If you get a rule wrong, you get a fine, and if you reach the end with too many fines, you lose the game — and therefore, you’re not ready to get on the real road.

And if you want to drive in Sierra Leone (as of 2013 at least, when the game was created), you needed to get the game first. As DW reported, the Sierra Leone Road Transport Authority (SLRTA) “says the game is now mandatory because of an increase in road accidents of the past few years.” Per Reuters, would-be drivers are expected to play the game for a couple of months (“or maybe just one if they’re smart enough”) before taking the actual driver’s test, although it is unclear how that was to be enforced beyond the driver’s test itself.

Per the few accounts out there, the kids don’t mind playing the game, either, although the cost — the equivalent of $14 — can be steep, given that a typical wage earner in the nation makes under $5,000 a year. That said, the game appeared to be somewhat effective; per DW, “countries like Ghana have already expressed interest in the game with the hope that it will also help motorists there to stay safe as well.

Bonus fact: The board game “Operation” is, nominally, about performing surgery on a patient, but it definitely does not teach you how to be a surgeon. And unfortunately for the game’s creator, it also didn’t make him a lot of money. John Spinello designed the game in the 1960s and sold it to Milton Bradley for $500 (or about $4,000 accounting for inflation) — but that wasn’t enough come 2014. Spinello, as the CBC reported that year, didn’t receive royalties as part of the sale to Milton Bradley, and was left unable to afford a $25,000 oral surgery bill. His friends — and fans of the game — were able to come to the rescue; per the CBC, they raised enough to cover his bills, and then some, via an online fundraiser.

Not a bonus “fact” per se but I thought it was really interesting: According to this webpage, Sierra Leone is the roundest nation in the world.

From the Archives: Why You Shouldn’t Take Advice From a Board Game: Unless it’s driving advice, I guess?