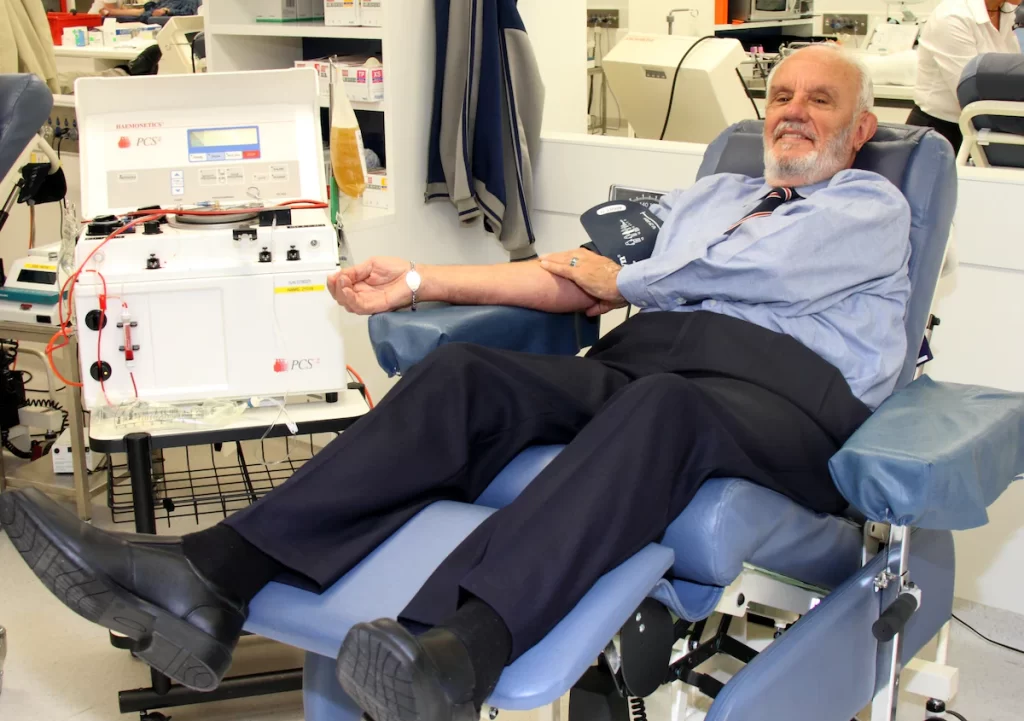

The Man With the Golden Arm

In the mid-1940s, an Australian teenager named James Harrison (above, much later in life) lost a lung to metastasized pneumonia. The procedure to remove the lung required major blood transfusions, thirteen liters in total. Harrison spent three months in the hospital recovering, and even at that young age, he understood that the extraordinary number of transfusions was fundamental in saving his life. He vowed that, as an adult, he would repay the favor and become a blood donor himself.

Through 2012, Harrison has fulfilled that promise—a thousand times over.

In 1954, soon after he began fulfilling his promise, researchers noticed something unusual about his blood. It contained a rare antibody, one that could unlock a cure for a disease that affects fetuses. The illness is called Rhesus disease, named after a protein also found in the blood of Rhesus monkeys. The protein, in and of itself, is typically not an issue for day-to-day lives; a person can be “Rh+” (that is, has the protein) or “Rh-” and, generally, not know or care.

But when a woman becomes pregnant, the presence of the Rhesus protein comes into play. If the mother is Rh- and the fetus inherits Rh+ blood from the father, the mother’s immune system may end up attacking the fetus’s bloodstream, seeing it as a threat. This can result in a wide range of medical complications for the fetus, ranging from being mildly anemic at birth to being stillborn.

Before discovering Harrison, doctors believed that the right type of antibody could be used to create a vaccine against Rhesus disease. Harrison had that antibody. Researchers asked him to undergo a series of tests to see if his blood could provide the cure and, after he obtained a $1 million life insurance policy to protect his wife in case anything went wrong, Harrison agreed.

Harrison’s blood provided the key to beating the disease. His blood plasma contained an extremely rare antibody, which was used to develop something called the Anti-D vaccine. This suppresses the Rh- mother’s immune system from attacking Rh+blood.

Since discovering that his bloodstream contains a life-saving ingredient, Harrison has been on a mission to make the most of it. He has donated plasma, on average, about eighteen times a year—roughly once every three weeks—since 1954. In May 2011, he made his 1,000th donation, easily a record. Each donation takes about forty minutes—that’s just under a month of his life dedicated to giving blood.

From the world’s perspective, that’s certainly a great deal. To date, hundreds of thousands of women—including his own daughter—have received the vaccine made from Harrison’s blood. In total, Harrison’s antibody has been used to treat more than two million babies who would otherwise have Rhesus disease. And millions more in the future will be saved by the antibody that he and others naturally produce.

Bonus fact: In around 2002, an Australian nine-year-old named Demi-Lee Brennan lost her liver to a virus. She received a transplant from a twelve-year-old only a day or two later, saving her life. For some reason, her body adopted the donor’s blood type as her own, changing it from O-negative to O-positive, as reported by the Sydney Morning Herald. Typically, organ transplant recipients require immunosuppressive drugs to prevent their bodies from rejecting new organs, as their bodies treat the life-saving additions as foreign invaders. But Brennan’s case was different. She not only adopted the donor’s blood type, but also his immune system. Hers is the only known case of such a phenomenon.

From the Archives: Type Cast: Why your blood type may matter more if you’re in Japan.