Royal Brew

At the close of the 1977 Major League Baseball season, the Kansas City Royals sat atop their division with 102 wins to just 60 losses. They were led by Hall of Fame 3B George Brett, DH Hal McRae, 20 game winner Dennis Leonard, and outfielder Al Cowens (who finished second to Rod Carew in MVP voting that year). But while they finished well, they were slow to start. On July 9th, they left Minnesota on the way to a three game set in Milwaukee to take on the Brewers. They lost the Friday night contest, 4-3, then won Saturday’s game, 6-0, and entered Sunday’s rubber match a game under .500 and in fifth place, five games behind the league-leading Twins.

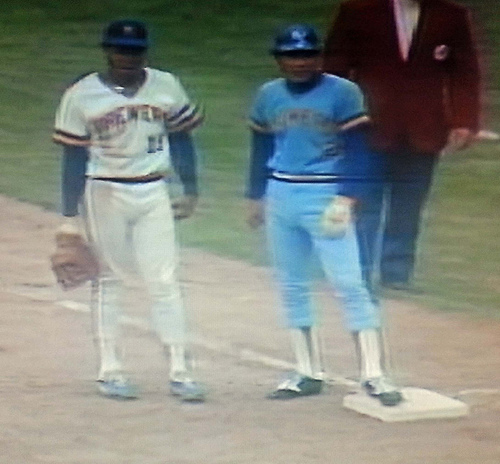

They’d lose Sunday’s game, too, by the score of 4-0. And if you were at the ballpark that day, you may have thought the Royals didn’t even bother to show up. No, not because of the score, but because of the uniforms. There were no Royals uniforms on the field that day.

They were stolen the night before.

As reported by the Milwaukee Sentinel the day after the game, the visiting team’s clubhouse at Milwaukee’s County Stadium was raided on Saturday night. The thieves took 52 jerseys (out of 60), 20 gloves, and a bunch of jackets, caps, and shoes. As the Sentinel pointed out, “for some reason, the Royals didn’t lose their pants.” But they had lost their shirts and a bunch of other stuff — and couldn’t cobble together anything which could be reasonably considered a uniform.

By rule, the Royals should not have been able to field a team; Rule 1.1 explicitly states (and then stated) that “no players whose uniform does not conform to that of his teammates shall be permitted to take the field.” That, quite simply, was impossible.

But the league office ruled that the show — or, in this case, ballgame — must go on. So the Brewers equipment manager sent over a few dozen Brewers jerseys. The home-team Brewers wore their white uniforms, while, as seen above, the away-team Royals donned baby blue Brewers tops with random numbers and the wrong names on their backs. Brett, whose jersey wasn’t stolen, donned his familiar “Kansas City” #5, while his teammate, McRae, also wore #5, but with “Brewers” on the front. Two players, outfielder Amos Otis and shortstop Freddy Patek, each wore #2, because that’s what the Brewers had lying around in their size. The Brewers’ starting pitcher Jerry Augustine, wearing #46, gave up a seventh inning single to Royals RF Cowens — also wearing Brewers #46. But they weren’t perfect doppelgangers. Because most of the batting helmets were left behind, Cowens had a “KC” on his helmet (see the KC helmet and Brewers jersey combo here) while Augustine’s cap had the Brewers’ logo on it.

The Kansas City equipment manager, per the Sentinel, estimated the cost of the stolen items to be about $3,500, or $12,000 in today’s dollars, accounting for inflation. The stolen items were never recovered.

Bonus fact: The Royals and Brewers also share a common origin — kind of. In the mid-1910s, the American and National Leagues (which now constitute Major League Baseball) were sued by the Baltimore Terrapins, members of an upstart league called the Federal League. The Terrapins claimed that by restricting players’ ability to re-join MLB teams after leaving to play in the Federal League, the American and National Leagues were violating antitrust laws. In 1922, the Supreme Court ruled that the Majors were exempt from antitrust laws, as baseball is a sport, not a business. But the Court left open the option for Congress to change that via legislation.

After the 1967 season, the Kansas City Athletics moved to Oakland. One of Missouri’s senators, Stuart Symington, was irate, and threatened to bring legislation to the floor removing baseball’s antitrust exemption unless Kansas City was awarded a new team. MLB responded by awarding teams to KC, Seattle, San Diego, and Montreal, to begin in the 1971 season, but Symington was not placated. He pushed for the teams to begin play in 1969, and was ultimately successful. Unfortunately, the Seattle team, the Pilots, wasn’t ready to start play. On Opening Day, their stadium, appropriately named “Sick’s Stadium,” only had 17,000 seats available (out of an expected 30,000), lacked a scoreboard, and had inadequate water pressure. The Pilots fell into bankruptcy at the end of the season and, just a few days before the 1970 season, were purchased by future MLB commissioner Bud Selig. Selig relocated the team to Milwaukee and renamed them the Brewers

From the Archives: Numbers Racket: Baseball’s (and other sports’) market in uniform numbers.

Related: “Ball Four” by Jim Bouton. An absolute classic, must-read book for any baseball fan, which in part, recounts the Seattle Pilots’ only season in existence.

Image via here.