The Financial Shenanigans Around Guantanamo Bay

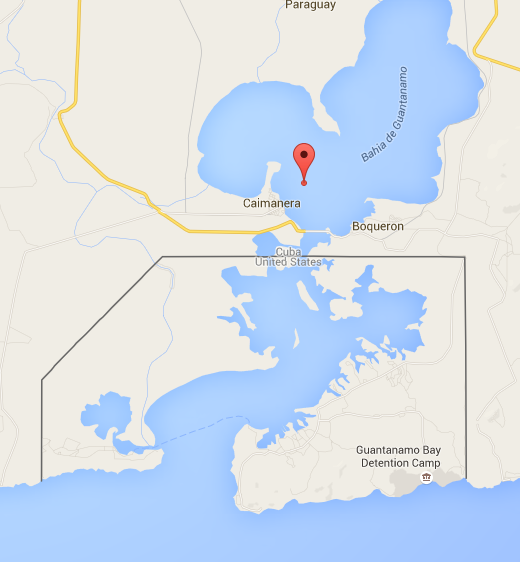

If you’re the Cuban government, that probably doesn’t sound like a good deal — at today’s exchange rates, the value of “2,000 gold coins” is closer to $140,000 than the pittance the U.S. pays them annually. But at the time, U.S-Cuban relations were copacetic and, for decades after, prices of gold were rather stable. The first part of that changed in 1959, when Castro came to power. Castro wanted the U.S. out of Guantanamo and, coincidentally, eliminated the position of “Treasurer General of the Republic.” The U.S. didn’t have anyone to send the checks to, and Cuba wasn’t going to let the Americans stay in Cuba peaceably, but the U.S. decided to keep sending the checks anyway.

But for some reason, Castro believed that by accepting the $4,000 and change, he’d be acknowledging the lease as a binding document in the eyes of the law — even though in Cuba, he is the law. Given that the amount of money changing hands was tiny anyway, Castro decided it was better to make it clear that he did not recognize the American’s claim to Guantanamo, so he never cashed the checks. (Well, he did in 1959; he claims it was an accident — an oversight from all the revolutionary activity going on at the time.)

So where do the checks go? As Reuters reported in 2007, Castro stuffs them into a desk drawer in his office — keeping every one. As a result, nearly a quarter of a million dollars — fifty-five years of checks, each for about $4,000 — is sitting in Cuba, unwanted by either side, tied up in checks that will likely never be redeemed.

Bonus Fact: Over the years, the U.S. and Cuba have tried a number of different ways to gain a strategic advantage over the other, often involving strange ideas and mixed results. In the earlier part of this decade, for example, the U.S. “secretly infiltrated Cuba’s underground hip-hop movement, recruiting unwitting rappers to spark a youth movement against the government,” according to the Associated Press. But, also per the AP, “the operation was amateurish and profoundly unsuccessful” while harming the hip hop scene more than the Cuban government. That latter part, in particular, made the U.S. efforts backfire, as the underground music world in Cuba was already rather anti-Castro.

Bonus Fact: Over the years, the U.S. and Cuba have tried a number of different ways to gain a strategic advantage over the other, often involving strange ideas and mixed results. In the earlier part of this decade, for example, the U.S. “secretly infiltrated Cuba’s underground hip-hop movement, recruiting unwitting rappers to spark a youth movement against the government,” according to the Associated Press. But, also per the AP, “the operation was amateurish and profoundly unsuccessful” while harming the hip hop scene more than the Cuban government. That latter part, in particular, made the U.S. efforts backfire, as the underground music world in Cuba was already rather anti-Castro.

From the Archives: Blame Cuba: The draft of an American plan to turn Americans against Cuba.

Take the Quiz: All about the Spanish-American War.

Related: “Guantanamo: An American History” by Jonathan M. Hansen. 4.3 stars on 16 reviews.