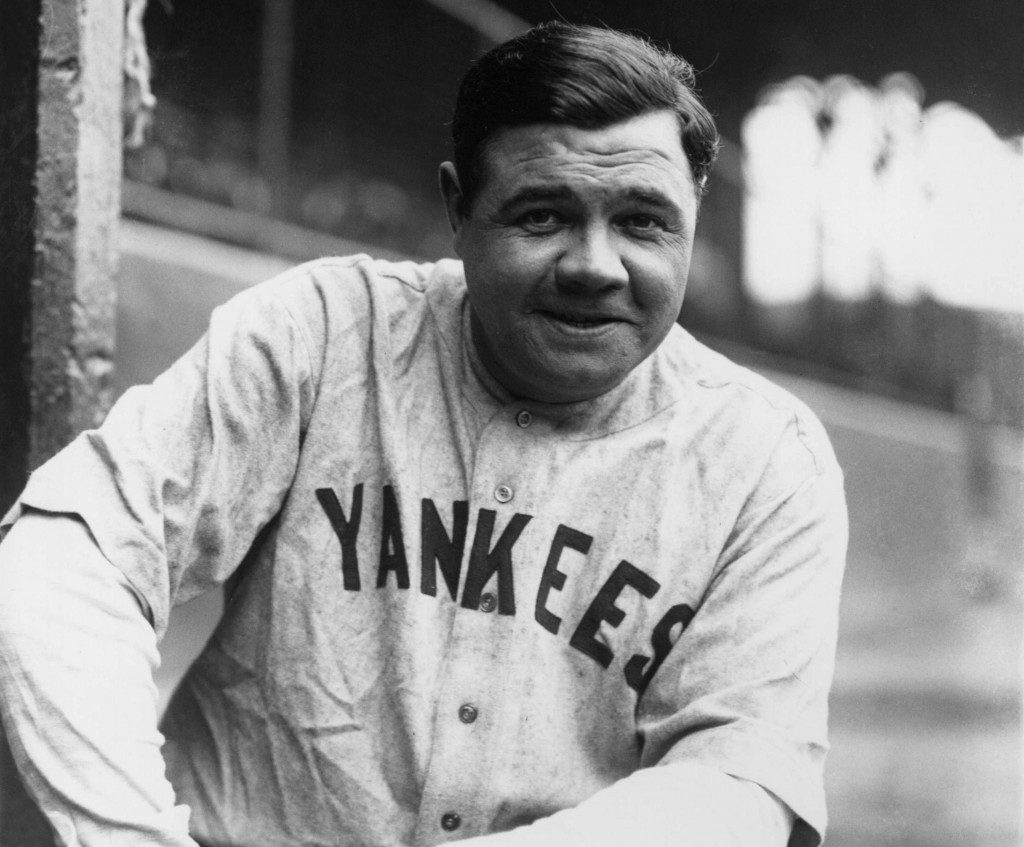

Babe Versus the Judge

On September 28, 1920, baseball players Eddie Cicotte and Shoeless Joe Jackson testified in front of a Chicago grand jury. The pair confessed that they and six other members of the White Sox had thrown the 1919 World Series in an effort to profit via an underground gambling circuit. The sport’s reputation in the public eye took a noticeable hit, and the league, per National League President John Heydler, wanted a man who would rule with an “iron hand,” showing Major League Baseball’s willingness to deal with such an infraction head-on. The league settled on federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who did just that: on August 3, 1921, he banned all eight “Black Sox” from the game for life, earning a reputation for being unforgiving.

Commissioner Landis’ next major move? To throw Babe Ruth out of the game, too.

Before the 1920 season, Ruth demanded a $20,000 salary from the Boston Red Sox. The Red Sox owner did not want to pay him what, at the time, was a very large amount of money for a baseball player. Instead, the Red Sox famously sold his contract to the Yankees. Ruth’s New York team paid up — the slugger ended up getting close to that amount, if not exactly what he demanded. But while Ruth was now pretty well off — $20,000 back then, accounting for inflation, would be more than a quarter million dollars today — most of his teammates were less so. And Ruth, despite being the face of the sport, was hardly paid like the stars of today.

Their solution: a practice known as “barnstorming.” Television was still experimental in 1921 (the first television station is generally regarded to be WRGB in Albany, which began broadcasting in 1928) which meant that watching Ruth and others play required a trip to a Major League ballgame. That required travel for most people, which could be expensive. So during the off-season, players would do the traveling, going to smaller towns and playing exhibition games The players would charge admission to these exhibition games as a way to earn supplemental income.

But starting in 1911, Major League Baseball banned players from the two World Series teams from barnstorming, wanting to keep the Series itself as a special moment in time. But this ban was weakly enforced, if ever. So, in October of 1921, fresh off their World Series loss to the New York Giants, Ruth and five teammates decided to go barnstorming. While this was a violation of the rule, Ruth, showing some caution, asked the Yankees general manager if it would be okay, and the GM said that it’d be fine — but that the slugger should check with Landis first.

Landis said no. And remember, Landis wasn’t the most flexible of commissioners — his “no” came with some actual heft.

Ruth, though, didn’t care. He and teammate Bob Meusel decided to do it anyway — Ruth apparently even refused to meet with Landis face to face, noting that he had to go to Buffalo, instead, to start the barnstorming tour. Landis, not to be trifled with, enforced the letter of the law. He suspended both Ruth and Meusel from the game, albeit not forever — the suspension went from start of the 1922 season until May 20th of that year.

Ruth returned to play on that date, having missed more than 30 games. The hometown fans took Landis’ side, greeting Ruth’s return unkindly; he was showered with boos by fans at the Polo Grounds, where the Yankees played their home games. (Yankee Stadium opened the next year.) The ban didn’t hurt the Yankees too much — they returned to the World Series, ultimately losing to the Giants again. But it did hurt Ruth’s stat line. That season was one of two times during a 14-year period from 1918 to 1931, inclusive, that Ruth did not lead the league in home runs. He finished third.

Bonus fact: Babe Ruth died in 1948 at age 53, having battled cancer for the final few years of his life. He was diagnosed in 1946 and a promising new treatment was in testing; Ruth’s doctors believed he’d be a good candidate for it. As a result, Babe Ruth became one of the first people, ever, to receive chemotherapy.

From the Archives: Swing and Miss: How Commissioner Landis handled a female pitcher who Babe Ruth couldn’t handle.