Backwards, Forwards

Spell backwards, forwards.

That may be a trick question. If you read it using normal syntax, you end up with the instruction to spell the word “backwards” forwards, which will give you the answer “b-a-c-k-w-a-r-d-s.” But, due to the comma, one could very reasonably read the command using a reversed syntax. In that case, the instruction would be to spell the word “forwards” backwards, resulting with “s-d-r-a-w-r-o-f.” Either answer is potentially correct — or, potentially, wrong.

In most cases, the resulting reaction to the paragraph above would be to take two aspirin for the headache it causes and say, “who cares?;” after all, there are very few reasons why one’s response to such a question would matter. But if you were an African-American living in Louisiana in 1964, whether you could get that answer “right” could determine whether you retained your right to vote — because many had to answer that question, and many others, before they were granted a ballot.

On March 30, 1870, Hamilton Fish, the U.S. Secretary of State, certified the 15th Amendment to the Constitution as ratified. The amendment states, in relevant part, that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” In short, it made it so states could not prevent African-American males (women had not yet gained suffrage) from voting, at least not directly. But until Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, many U.S. states (particularly southern ones) found indirect ways to disenfranchise blacks. One of those ways? Literacy tests. States administered tests which were purportedly designed to keep uneducated males off the voter rolls, but were actually intended to make it difficult for African-Americans to get on those voter roles, regardless of their actual education. The Louisiana exam from 1964 is one such example.

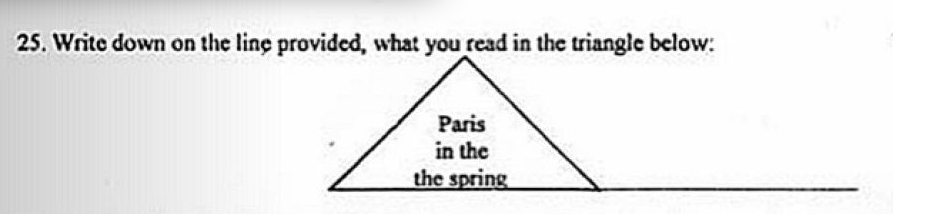

The test, available in full here (via Slate), was thirty questions long. Some had vague instructions, like the backwards/forwards question (#20 on the linked-to exam). A few, such as question 15 (“write the word ‘noise’ backwards and place a dot over what would be its second letter should it have been written forward”) are difficult to parse and take a good deal of time simply to read. Still others were intentionally designed to trick the reader, such as question number 25, below.

(If you don’t see the trick, read each of the words in the triangle slowly. Starting with the last word and working your way backward may also help.)

Test takers had only ten minutes to complete the exam — that’s 20 seconds per question. Get even one answer wrong? That meant you did not pass, and therefore, could not vote. As designed, almost everyone would, therefore, fail the exam.

But the exam wasn’t administered to everyone — anyone who could “prove a fifth grade education” (often something de facto limited to whites) did not have to take the exam in the first place. Second, as Slate points out, “the (white) registrar [of voters] would be the ultimate judge of whether an answer was correct” or, one assumes, whether the ten minute clock had expired. In practice, whether the test taker wrote “b-a-c-k-w-a-r-d-s” or “s-d-r-a-w-r-o-f” didn’t matter — all that mattered was the color of the test-taker’s skin.

Bonus Fact: Almost all U.S. jurisdictions use an election system called “first-past-the-post,” where the candidate with the most votes wins the election, even if he or she doesn’t have a majority of the votes. Louisiana is a notable exception. For state-level races (e.g. governor), Louisiana has a jungle primary — all the candidates, regardless of party, run in the first round of elections. If no candidate receives a majority of the votes, the top two vote-getters, also regardless of party, face off against each other in a second round of voting. This can lead to an odd result, such as what occurred in 1983. Buddy Roemer led with 33% of the vote in the jungle primary for governor and incumbent Edwin Edwards received 28%, coming in second. Edwards withdrew from the race, automatically handing the governorship to Roemer — despite the fact that the latter had failed to convince two-thirds of the state to vote for him.

From the Archives: Coup D’USA: Another attempt to suppress civil rights.

Related: “American Nightmare: The History of Jim Crow” by Jerrold Packard. 14 reviews, 4.4 stars.