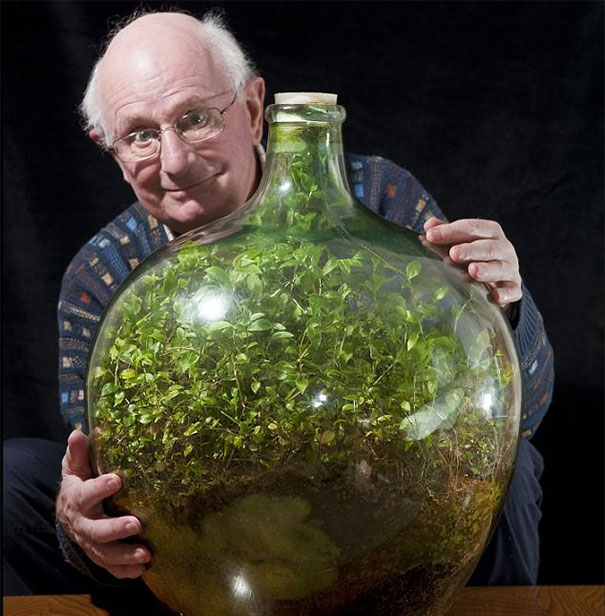

David’s Garden

The plant pictured is the creation of David Latimer, a retired electrical engineer (also pictured). It lives in a bottle under a staircase at Latimer’s home, in the English village of Cranleigh, Surrey. It’s a species of spiderwort, but as it lives in a corked-up bottle, it doesn’t flower like spiderworts often do. As a result, the bottle looks like a container full of overgrown weeds. But it’s not. It’s an entire world.

And it has been for a long time.

The thing above is a “bottle garden.” The concept has been around for generations and is pretty simple. Put some dirt and some plant seeds in a bottle (hence the name). Add a bit of water and put a stopper in the bottle. Then place the bottle in an area that gets a good amount of sun, and, over time, you’ll get a little garden.

The plant won’t require a lot of upkeep because except for sunlight, nothing gets in and nothing gets out; as a result, it is an ecosystem all to itself. The plant creates energy from the sunlight via photosynthesis, using up carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen into the bottle. When parts of the plant die, bacteria in the soil use the oxygen to break down these dead parts, releasing carbon dioxide and completing the circle. The water cycle is similarly self-refueling: whatever water the plant takes in through its roots ultimately transpires out of its leaves, condenses on the inside of the bottle, and drips back into the soil.

In theory, therefore, a bottle garden can persist, undisturbed, indefinitely — even though it is (sunlight aside) cut off from the outside world. But in practice, that’s rarely the case. Putting aside the fragility of a glass bottle with a cork stopper, it takes discipline on behalf of the bottle gardener to let nature find a way. Plus, these gardens can be kind of boring, and you may just end up throwing it out after a while.

Which brings us back to the garden pictured above. What makes Mr. Latimer’s garden special isn’t what he’s done with it, but rather what he hasn’t — because he hasn’t done much. Latimer originally planted his bottle garden in 1960, sealed it, and let it sit — for twelve years. In 1972, according to the Daily Mail, thinking the plant may be a bit too dry after all of those years, “put in about a quarter of a pint of water.” Then, he resealed the bottle — and it’s remained sealed to this day. And yet, it still grows and regrows year after year.

For the last forty-plus years, Latimer’s bottle has been separated from the outside world, thriving in its own, self-contained ecosystem with no end in sight. In fact, it may outlive Latimer himself. If so, Latimer has a plan. The plant will go to his children if they want it; if not, he’s going to donate it to the Royal Horticultural Society.

As for everyone else? Well, you’re on your own — but if you want to build your own bottle garden, here’s a video explaining how.

Bonus fact: Every once in a while, you’ll come across a bottle of brandy with a full pear sitting in the bottle. (Here’s a picture of some examples.) How do you put a pear in a bottle? You don’t — you grow the pear in the bottle. As NPR explained, “workers fasten the bottles securely to nearby branches, and then wait a few months for each tiny pear to grow and ripen in its own little glass greenhouse.”

From the Archives: Beer Bricks: Another way bottles can build homes.

Take the Quiz: Finish these “garden path” sentences. Take your time on this one — it’s fun and you can figure out most of them that way. (By the way, a “garden path sentence,” if you’re unfamiliar with the term, is, per Wikipedia “a grammatically correct sentence that starts in such a way that a reader’s most likely interpretation will be incorrect; the reader is lured into a parse that turns out to be a dead end or unintended.”)

Related: An “EcoSphere Closed Aquatic Ecosystem” — a small, self-contained ecosystem in a glass sphere. 4.3 stars on average from nearly 800 reviews. It’s neat; it’s “a completely enclosed, self-sustaining little world” featuring little shrimp and some plants and other stuff. It lasts about two or three years, though, unlike Latimer’s plant system.