How a Ouija Board Can Protect You from a Lawsuit

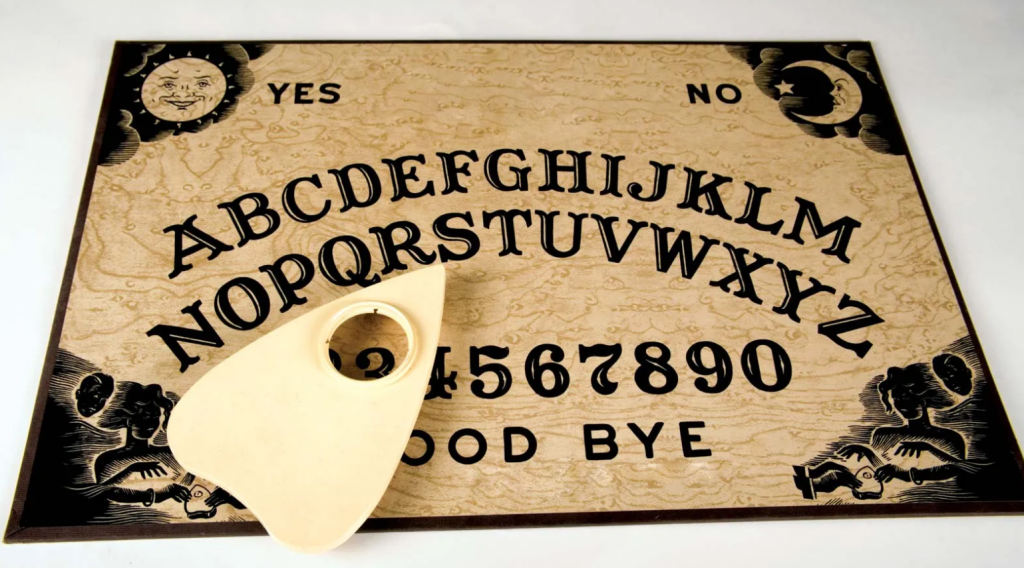

Pictured above is a Oujia board. If you’re not familiar with it, the Ouija board is a mass-produced “game” that basically a wooden plank with the letters of the alphabet, numbers zero to nine, and the words “yes,” “no,” and “good bye” printed on it. It comes with a little heart-shaped piece of plastic or wood called a “planchette,” which purportedly focuses the energy of those who touch it. When the users place their hands on the planchette, nothing happens unless the users push the planchette.

But that’s not how the Ouija board is marketed. It’s said to be a way for those of us on Earth to communicate with those who have left for the great unknown; as the story goes, if the planchette moves, it’s actually being powered by the spirit of a deceased person. The long departed loved one is there to answer the questions that those of us still alive could never know, like what the winning numbers of this week’s Mega Millions jackpot is going to be or where I left my car keys.

In other words, the two most important letters of the Ouija board are “BS,” as that’s the only thing it’ll really tell you (a scene from Awakenings notwithstanding). But in 1921, that was a matter of justice. Specifically, that year, a court in the Chicago area had to make sure that twelve specific men were willing to swear, under penalty of perjury, that they didn’t believe in Ouija-powering ghosts.

The story started two years earlier, in late 1919. Two couples—the Yosts and the Walters—were friends who spent time together fairly regularly. However, as the Chicago Tribune noted, that relationship went south when Mrs. Walter ran for a leadership role in their local community group. She expected Mrs.

Yost to support her efforts but found the opposite was true; Mrs. Yost not only didn’t throw her support behind Walter, but she ran against her—and won. An upset Mrs. Walter decided to investigate. And what she found was weird.

On the night of November 10, 1919, the Yosts home had been burglarized..The thief, per the Tribune, “looted of a small sum of money,

a bunch of groceries, and twenty-five pounds of raisins.” (The extraordinary amount of raisins, as you’ll see, in the bonus fact, is not the weird part of the story.) Such crimes were rare in their suburb and the burglary became the talk of the town. Everyone wanted to know who stole the Yosts raisins — but the police had nothing to go on. The identity of the culprit remained unknown for weeks. And when the Yosts invited some friends over for Thanksgiving dinner, the conversation at the table eventually turned to the question: whodunit?

That’s when one of the guests had an idea: let’s confer with the dead. The Yosts broke out a Ouija board and one of the guests asked the board who robbed the Yost’s home, and, according to Mrs. Yost, the planchette began to move across the letters, spelling out “the Walter family.” News of the paranormal confession spread, and when voting day for the local community group came up, Mrs. Walter’s reputation was besmirched, likely causing her to lose the election.

The Walters, understandably upset that they were now considered thieves by their neighbors and former friends, demanded an apology from the Yosts, but they declined — the Ouija board said what the Ouija board said. So, the Walters sued. In general, you can’t accuse people of crimes without running the risk of liability, and the Walters demanded compensation for their sullied names. The lawsuit demanded a hefty $10,000 in damages—the equivalent of more than $150,000 today. And it went to trial.

At first, the Yosts wanted to call the Ouija board as a witness, but the judge quickly shot down that avenue of defense. In picking jurors, the Walters’ attorney asked the court to reject any prospective juror who believed in ghosts, and the court agreed. As The New York Tribune explained, at least six prospective jurors were dismissed because they were too willing to believe that ghosts were real. The case eventually proceeded, as the Tribune described, with a jury of “twelve good men and true who are sure that no such thing as a spirit world exists and that Ouija boards are merely something with which to while away time.”

But the Yosts argued that they didn’t need to actually prove ghosts were real to win — all they needed to establish is that Mrs. Yost didn’t make any defamatory statements against the Walters: it was the Ouija board.

The judge, basically, agreed with that standard. According to the Independence Daily Reporter, the judge “instructed the jury that if Mrs. Yost said the Ouija board had revealed Mrs. Walters as the alleged robber, Mrs. Yost was not guilty” but “if Mrs. Yost made the remarks herself, however, and neglected to quote Ouija,” the Walters could collect. The jury found that Mrs. Yost cited the Ouija board every time she mentioned Mrs. Walter’s role in the theft, and the Walters lost to what was perhaps the world’s first-ever — and likely last-ever — successful “defense by Ouija board.”

Bonus fact: Why steal twenty-five pounds of raisins? And, in the case of the Yosts, why have twenty-five pounds of raisins in the first place? Today, you probably wouldn’t, but as 1920 approached, so did Prohibition. And if you have enough raisins, you’re on your way to making a type of moonshine called “raisin jack.” While the newspapers didn’t spell it out, chances are the Yosts (and the real thieves) were planning to make some illicit spirits in their spare time.

From the Archives: The Grape Crusader: A weird U.S. law about raisins.