How Did the Squirrel Cross the Road?

The old (and kind of nonsensical) joke asks, “why did the chicken cross the road?” And it kind of works as a question because while chickens can cross roads, they don’t do so very often. Chickens usually live on farms and while there are typically some roads near farms, there aren’t as many roads as one would find in more suburban or urban areas. So when a chicken crosses a road, it’s strange enough to warrant the inquiry.

Squirrels, however, demand no such investigation. Living in the suburbs and our cities, squirrels cross roads often. And the reason they do so is simple: they’re hungry. Trees can be on either side of a road, and trees give off nuts. If a nut-hungry squirrel is in need of a meal or is preparing for winter, it’s going to dash across a roadway without much hesitation. And unfortunately, that decision doesn’t end well. Which is why a guy named Amos Peters of Longview, Washington decided to build a bridge.

For squirrels.

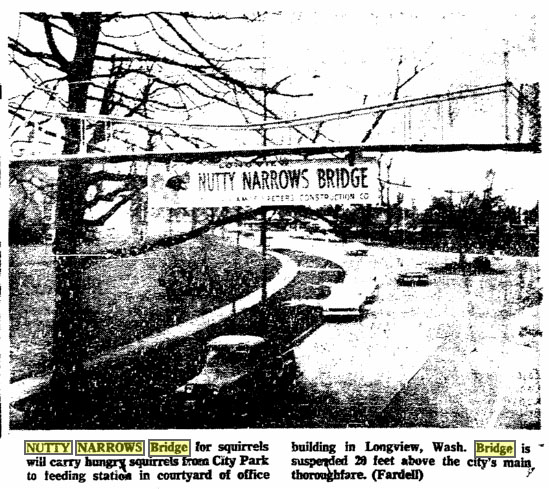

The image above (via Flickr user Skrewtape) shows the bridge in question, but it may not do it justice. In 1963, Peters owned a construction company in Longview. His office window, as Roadside America summarized, “had a ringside seat to a ceaseless procession of hit-and-run fatalities on Olympic Way. It was a busy street with tall trees, part of a somewhat confusing circle, with other busy avenues converging in front of Longview’s public library.” So Peters got to work, looking to save the lives of some squirrels and himself from viewing the trauma of their untimely deaths. His solution, which he named the “Nutty Narrows Bridge,” now hangs 29 feet over Olympia Way between Maple Street and 18th Avenue in Longview, in case you’re ever in the area. Here’s a newspaper clipping from when it opened (via the Washington Department of Archaeology & Historic Preservation) to give you an idea of just how high it is above the traffic.

And yes, the bridge actually worked. Per Atlas Obscura, “squirrels were soon using the overpass to cross the road safely” (although there were definitely some who took the lower, more treacherous path). And originally, at least, it wasn’t that expensive, either. According to Longview’s official website, Peters “built the 60-foot bridge from aluminum and lengths of fire hose,” at a cost of about $1,000 at the time (or about $8,500 in today’s dollars). That bridge lasted about twenty years; it was repaired in 1983. In 2007, the town moved the bridge about 100 feet down the road — while the bridge was fine, the trees from which it was suspended began to rot and could no longer hold the weight of the squirrels making their way safely across the road.

We don’t know how many squirrels crossed the bridge over the decades — Longview doesn’t have a squirrel census, after all — but the town definitely believes that the Nutty Narrows has been a success. Over the years since, Longview has built another four squirrel bridges, connecting trees and treats without risk of squirrel death. And in 2014, the Nutty Narrows Bridge was entered into the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places. Peters was not alive to see his creation get this honor, but the town memorialized him regardless; as seen here, there’s a statue in town — a statue of a squirrel — in his honor.

Bonus fact: While Longview, WA doesn’t have a squirrel census, that’s not as ridiculous as an option as one may think. Each year, volunteers gather in New York City’s Central Park, hoping to estimate the number of squirrels that reside within the urban expanse. Per the organization’s website, as of 2019, “there are an estimated 2,373 Eastern gray squirrels in Central Park.”

From the Archives: A Squirrely Mission: Maybe Amos Peters was part of a secret spy network? Okay, probably not.