I Guess You Could Say They … Excel

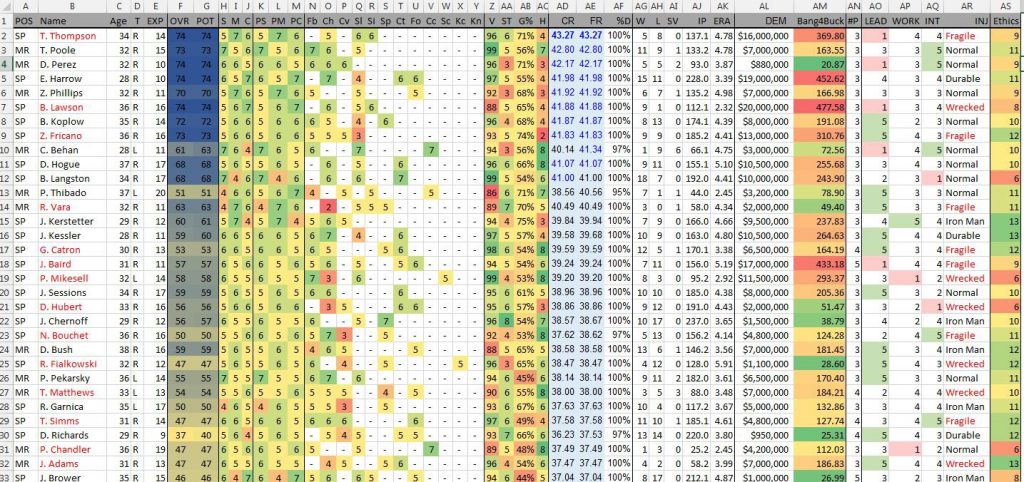

Pictured above is a complicated-looking Excel spreadsheet, or, for many of us, the stuff that nightmares are made of. Excel, the spreadsheet software made by Microsoft, is a really powerful tool that lets helps you manipulate data in all sorts of ways — if you know how to use it. But if you don’t, it can be overwhelming and confusing, as even small changes to your tables can cause the software to yell at you with things like #DIV/0 or ###### or the dreaded #REF! error. Many of us avoid Excel like we would the plague.

Those who are really good with Excel — the people who dream of pivot tables — they’re basically magicians. Unsung ones, though. Or they were until — until the fall of 2021.

That’s when the Financial Modeling World Cup Open — or the World Cup of Excel — made its debut.

Starting on November 13, 2021, and into December, thousands of Excel magicians forked over a $50 entrance fee and entered into qualifying rounds. The participants were given 30 minutes to complete a very complicated modeling task, using only Microsoft spreadsheet software and their wits. The 128 competitors with the highest scores advanced to the main event: a real-time, live-streamed face-off against a specific opponent in a single-elimination tournament. After four rounds spaced over a few days (to account for differences in time zones), the Excel Open reached its main event: a two-and-a-half-hour Excelfest featuring some of the greatest athletes (?) in the world.

You can watch it here — and join the nearly half a million other people who have checked out the video. The first fifteen minutes or so are introductions, so you may want to skip that and head right to the 16:47 mark, where you’ll be greeted with the rules for the round of 8 — and you’ll see, right away, that this isn’t the Excel task you’re used to. Competitors were asked to create a “ride planning and traffic forecasting application” for a fictional ride-sharing company, and the map provided to the participants included a lot of icons of cars and buildings and the like — but, as host Bill Jelen notes on the stream “absolutely no numbers.” Competitors were then given a series of questions to answer using the map and Excel’s tools — the more questions they get right, the more points the players get. At the end of 40 minutes, if you had more points than your opponent, you advanced to the next round. (Why the Cup organizers decided to make it head-to-head at this stage is strange; as seen here, the third-best finisher was eliminated because he had the unfortunate luck of being paired against the top finisher in the round.)

In the final round — it starts at 1:51:06 — Canadian Micahel Jarman faced off against Australia’s Andrew Ngai in a task titled “Knights and Warriors,” modeling “possible outcomes between [ . . ] two armies under various scenarios.” The two were neck and neck for the first 12 or so minutes of the 30-minute match, tied at 120 each. But then Andrew began to break away. He ultimately won, dominating Michael by a score of 734 to 280.

The competition was popular enough that it not only earned the Cup another season’s worth of competitors but also some TV coverage — on ESPN3. And it made for some rather compelling television, as the Atlantic recounted. Ngai, the reigning champ, was facing off against a newcomer, American Brittany Deaton, and Deaton was winning, 390-316. But with about three minutes left, Ngai took the lead — and then, as the Atlantic states, “this is when things got really wild.” You can watch the last 90 seconds or so here, but the Atalntic’s recap below does it justice:

As the clock approached one minute, Deaton submitted a batch of correct answers and shot up to 610 points. Seconds later, Ngai leapt to 603. Then, Deaton accidentally changed several correct answers and dropped to 566, ceding the lead to Ngai … who promptly began hemorrhaging points himself—592 … 581 … 570 … 559. Fans were losing their minds. “Undo!” one commentator exhorted. “Control Z!” They both did, and suddenly we were right back to Deaton 610, Ngai 603. “Ave Maria!” cried another commentator. Ave Maria indeed: Still behind with five seconds left, Ngai went for the Hail Mary, entering what he would later admit was a random guess and, miraculously, guessing right. A buzzer-beater! Ngai 615, Deaton 610.

Ngai ended up winning the finals as well, retaining his title and taking home the $10,000 grand prize.

If you want to try to beat him this year, great news: you still can. Registration for the 2023 Cup is open right now (with a 30% early bird discount!), here. And if you’re not sure yet but want to give one of the tasks a try, you can do that, too; the Financial Modeling World Cup offers sample tasks from prior competitions for $20, here.

Bonus fact: As of 2017, Microsoft Excel tops out at 1,048,576 rows, according to Mental Floss. How long would it take to scroll all the way down? That year, a YouTuber named Hunter Hobbs decided to find out — he challenged himself to hold the down arrow key until it hit the bottom and recorded the ultra-mundane task for all of us to see. The end result? A really boring video with a run-time of nine hours, 38 minutes, and two seconds.

From the Archives: The History of the Three-Finger Salute: Why We CTRL-ALT-DEL our way through computer problems.