Koreikashakai Prisoners

If one were to rank nations by their incarceration rates, the United States would easily top that list with over 700 people behind bars per 100,000 in the population as a whole. Russia incarcerates about 500 per 100,000, Singapore just under 250, France about 100, and well toward the bottom is Japan at 55. (Here’s the full list) And while Japan seems extraordinarily low, it could be even lower. A crime wave which began in around 2009 jumped the incarceration rate from 48 per 100,000 to nearly 60 per 100,000.

The crime? Shoplifting. The criminals? The elderly.

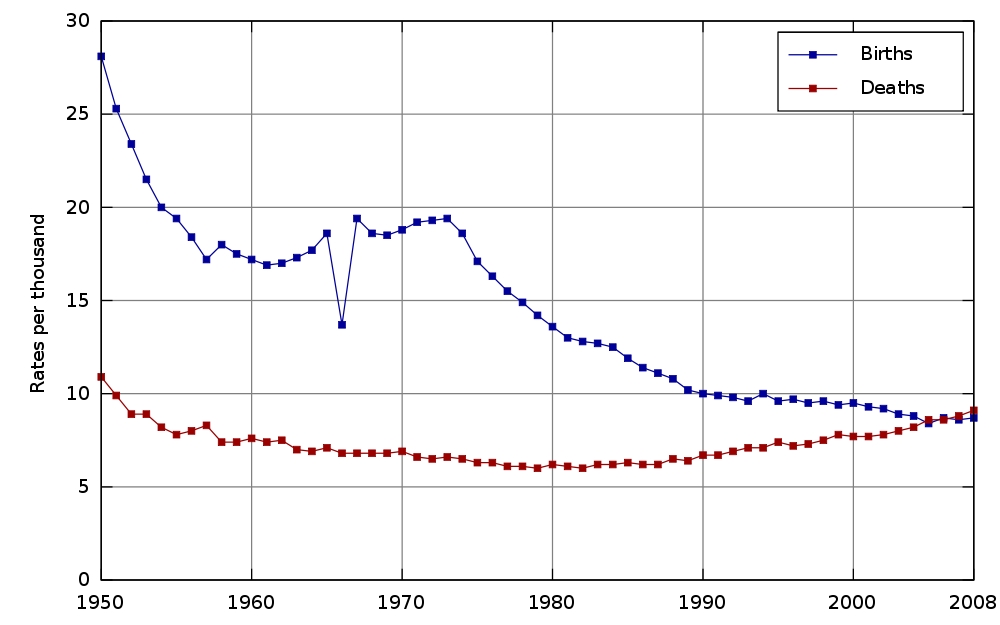

Japan is widely believed to have the oldest population, with 20 to 23% of all Japanese age 65 or older and with over 10% age 75 or older. (By comparison, about 13% of Americans are 65 or older.) The rapid gain of population share by the elderly is stark, compared to other nations (as seen here), and this transformation of the population’s demographics is called “koreikashakai,” literally “a high-aged society.” The reasons for this are varied. Japan has a low birth rate, with only 1.5 live births per woman as of the year 1993 and going down — it was 1.39 per the 2012 CIA World Factbook. (The replacement fertility rate — that is, the rate needed to maintain the population — in an industrialized country is typically around 2.1; 1.39 is incredibly low.) On the other hand, Japan’s mortality rate is low, leading to higher than typical life expectancies. The two rates are criss-crossing, leading to a shrinking and rapidly aging population.

As graphs go, that’s a scary proposition. And it’s also scary if you’re one of the elderly, who is finding fewer and fewer working-aged people able to provide elder care or companionship for you.

Which is why some of the elderly have taken up a life of petty crime. Many, such as the 50-something man in this BBC video, simply do not have enough money to eat. And he’s a rarity — he’s notably younger than most shoplifters. The store manager the BBC interviewed estimated that 80% of the shoplifters he comes across (five or six each week) are in their sixties if not older. An Associated Press reporter spoke with an inmate in his late sixties who was finishing up a three-and-a-half year sentence but did not want to be released: “I’m worried that there would be no work for someone like me.” And the available prison amenities — to use the term loosely — aren’t terrible. Inmates get three meals a day and a “twice-weekly bath” as well as shelter in a generally safe environment.

But economic security isn’t the only reason for the theft-to-get-incarcerated movement. In 2009, the Japan Times reported on a study conducted by the Tokyo police which found that nearly a quarter of the shoplifting elderly were feeling lonely. Shockingly, 40% of those 65+ shoplifters surveyed by the police said they live alone and more than half said that they did not have any friends at all.

Bonus fact: Brazil, in an effort to combat illiteracy among prison inmates, offered a books-for-early release program in 2012. Per the Globe and Mail, reading a book (and writing a book report on it) could earn an inmate four days off his or her sentence, with a maximum reduction of 48 days earned each year.

From the Archives: Stealing One’s Own Work: A person who went to prison for stealing his own research.

Related: “The Steal: A Cultural History of Shoplifting” by Rachel Shteir. 13 reviews, 4.1 stars, available on Kindle.

Graph via Wikipedia entry on aging in Japan.