Leaving Berlin Behind

The First World War claimed the lives of at least 15 million people, wiping out roughly one percent of the world’s population. While most of the fighting occurred in Europe and Russia, the casualties — like the name of the war suggests — were spread across the world, with many different nations bringing servicemen to the battlefield. As countries from afar sent their soldiers into Europe to fight, many at home — far from the war’s desolation — felt the world’s divide in many different ways. Canada, for example, was divided over Berlin.

Berlin, Ontario.

Berlin, Germany was the capital of the German Empire during the war (and of the successor nation, the Weimar Republic, shortly thereafter). Berlin, Ontario, on the other hand, was a small Canadian city of roughly 15,000 people. It was named after the much larger and older city in Germany. Its founders were Mennonite settlers from Pennsylvania, and of Germanic descent, but were generations removed from the immigration to the New World. Nevertheless, the war caused much of the city’s German aspects to fall into disfavor, as anti-German sentiment swept over much of North America. (For example, in 1914, a bronze statue of Kaiser Wilhelm, then Emperor of Germany, was taken from a local park and thrown into a lake.) On top of that, the small but significant remaining Mennonite community were pacifists, and therefore unwilling to participate in the war — something which likely was erroneously ascribed to their national origin.

Many in Ontario were embarrassed. The appearance that Berlin was a little piece of Germany in a country at war with that nation was too much to accept, as strange as that may sound to modern ears. Being a symbolic problem, a symbolic solution was in order. That solution: change the town’s name.

As the Library and Archives of Canada reports, in 1916, Berlin’s Board of Trade pushed for a name change:

The Board of Trade argued that the name Berlin hurt business and gave the impression that its citizens were sympathizers of the enemy cause in Europe. It was suggested that the act of changing the name of the city would be a tangible symbol of its citizens’ patriotism and would boost the city’s profile across the Dominion. Many Berliners supported maintaining the name of the city, as it reflected a proud tradition of growth and prosperity for German, and non-German, Canadians alike. Those citizens who supported the status quo were immediately perceived, by those who wanted change, as being unpatriotic and sympathizers with the enemy. Violence, riots and intimidation, often instigated by imperialistic members of the 118th Battalion, were not uncommon in the months leading up to the May 1916 referendum on the issue.

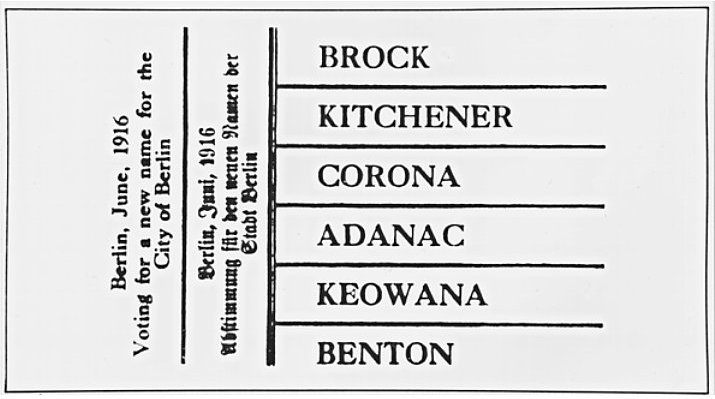

Those who objected to the name change were quickly marginalized, and the name change came to a vote as seen on the ballot below.

Those objecting made their voice heard simply by not showing up. According to Wikipedia, only about 900 of the city’s 15,000 citizens made it to the polls. Despite only collecting 346 votes, Kitchener (after a famous British field marshall) prevailed as the new name. The silent majority immediately petitioned the Ontario legislature to intervene, providing 2,000 signatures of citizens wishing to keep the name “Berlin,” but their pleas were denied. On September 1, 1916, Berlin officially became Kitchener. But not everyone was willing to go along with the mandate, even after legal avenues to prevent the change were exhausted.

The next method of protest: the mail. Throughout Canada, Berlin sympathizers — Berlin, Ontario, that is — addressed letters to “Berlin” and not “Kitchener,” requiring the post office to make a choice: deliver the mail and keep the old name intact, to a degree; or force the issue and fail to deliver mail even though the recipient’s location was clear. The post office issued memoranda threatening to do the latter (see one here), but the Postmaster General proclaimed that mail to Berlin would be delivered as if it were addressed to Kitchener. Not everyone appreciated the proclamation, though. Other municipalities, such as the city of Kingston, Ontario, petitioned the Canadian government (as seen here), asking that it overrule the Postmaster General and stop the flow of mail to Berlin.

Ultimately, this wasn’t necessary. Over time, the Berlin-devotees gave up, and the name stuck. A handful of Canadian activists managed to wipe Berlin off the map.

Bonus fact: A “Berliner” isn’t just a person from Berlin, but also a type of food which closely resembles a jelly doughnut. Most people know this because in June of 1963, American President John F. Kennedy famously stated “Ich bin ein Berliner” during a speech, hoping to say “I am a Berliner” as a message of solidarity with West Germany during a contentious part of the Cold War. And, as the story goes, JFK flubbed the grammar, accidentally saying that he was a “jelly doughnut” instead of a “person from Berlin.” It’s a great story, but it’s a myth. JFK’s grammar was fine, and it’s unlikely at best that any German speakers thought he was claiming to be dessert.

From the Archives: The Christmas Truce: British and Germans take a day off from World War I.

Related: “Let the Word Go Forth: The Speeches, Statements, and Writings of John F. Kennedy 1947 to 1963.” Five stars on three reviews.