Pass Out the Vote

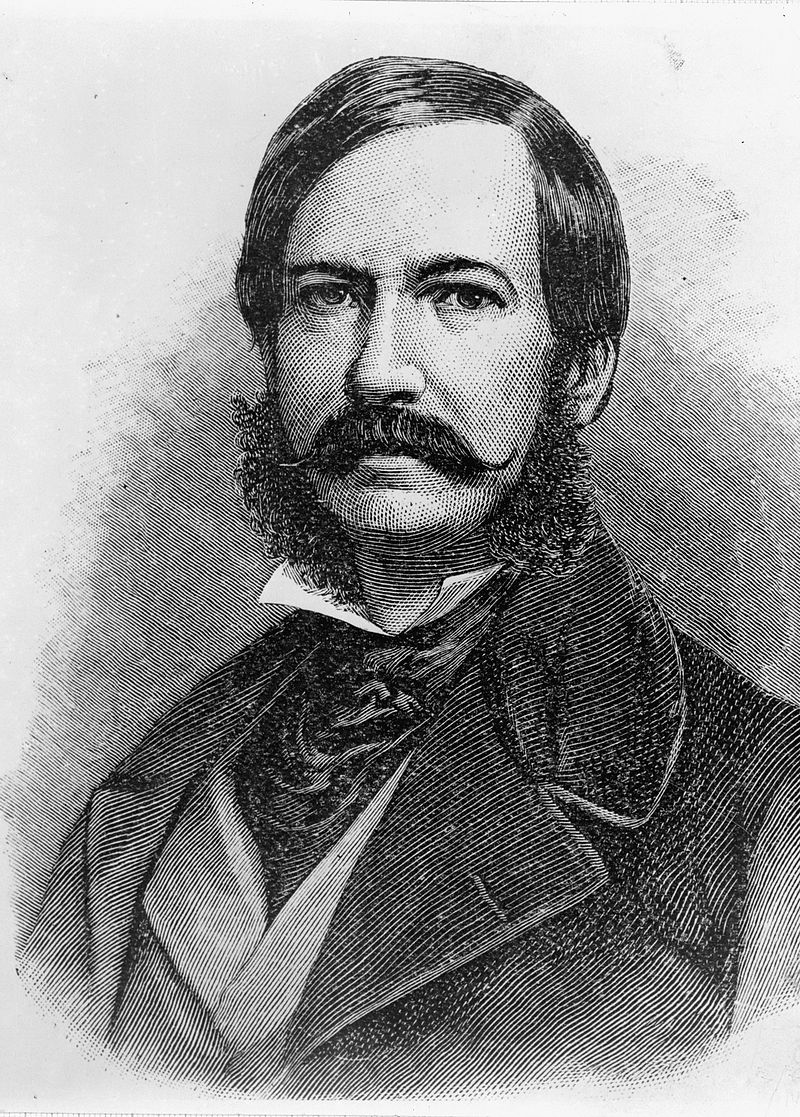

Edward Jerningham Wakefield, pictured above, was born in London in June of 1820 and was an early English colonist in New Zealand. His father, a politician named Edwin Gibbon Wakefield who advocated for colonial expansion, and at about age 18, Jerningham — he went by his middle name — traveled with his father to Canada on a secret mission to unite Lower and Upper Canada into one political unit. The colonization bug hit Jermingham and, shortly thereafter, he joined his uncle, Colonel William Wakefield, on an expedition to New Zealand. Jerningham was supposed to only be in New Zealand for a few months, scouting out areas for future British colonies, but became enamored with the area. He remained in New Zealand for four years, returned to London in 1844 where he advocated for future colonization of his adoptive home, and returned to New Zealand permanently in 1850.

When New Zealand formed a parliament in 1853, he was among its first members, serving one term. He returned to private life thereafter but ultimately sought political office again, and in 1871, Jerningham Wakefield was, for a second time, elected as a Member of Parliament (MP). But he proved unpopular. When he was up for re-election four years later, he was one of six men on the ballot striving for one of three seats. Wakefield came in fifth.

His allies in Parliament were probably very happy about this — it meant they didn’t have to lock him in the closet any more.

Okay, it wasn’t a closet, but close enough.

Wakefield had a drinking problem; his entry in Teara, the encyclopedia of New Zealand states that “his later life was clouded by alcoholism and disgrace,” and the alcoholism was a notable part of his second term as an MP. At times, he would drink so much that he became unable to vote on legislation. Incredibly, he was not alone here — there were a few other MPs for whom the term “drop dead drunk” was only barely an exaggeration — and as a result, his sober colleagues needed to find a solution. According to the book “Grog’s Own Country: The Story of Liquor Licensing in New Zealand,” the answer was simple: the MPs in question were “locked up by Whips [legislative leaders, not these] in small rooms to keep them sober enough to stand up for crucial [matters].”

But it didn’t end there.

Wakefield’s political allies must have thought they had a fool-proof plan — by keeping Wakefield behind lock and key in a room without an alcohol, they had a vote at the ready when the time came. But Wakefield’s team made an error which only Santa Claus would have noticed: the otherwise-inaccessible room that housed Jerningham had a chimney. “Grog’s Own Country” continues: “on one occasion, political opponents tried to defeat the purpose of the incarceration by lowering a bottle of whisky to a prisoner (it was E.J. Wakefield in 1872) down the chimney on a piece of string.”

According to one blog, the ploy almost worked. Wakefield drank too much initially, falling “paralytic” under the table — but he was able to recover in time to vote.

Bonus Fact: Is it “whisky” or “whiskey”? Both, depending on how you look at it. According to Grammarist, “whisky usually denotes Scotch whisky and Scotch-inspired liquors, and whiskey denotes the Irish and American liquors.”

From the Archives: The Prohibition Prescription: How whisky made Walgreens a pharmaceutical powerhouse.

Take the Quiz: Identify these countries that aren’t New Zealand.

Related: “Grog’s Own Country: The Story of Liquor Licensing in New Zealand” is out of print and you can’t buy whisky or whiskey on Amazon, but these ice cube-replacing rocks are, pardon the pun, cool.