Ten Thousand Reasons to Read Before Hitting “I Accept”

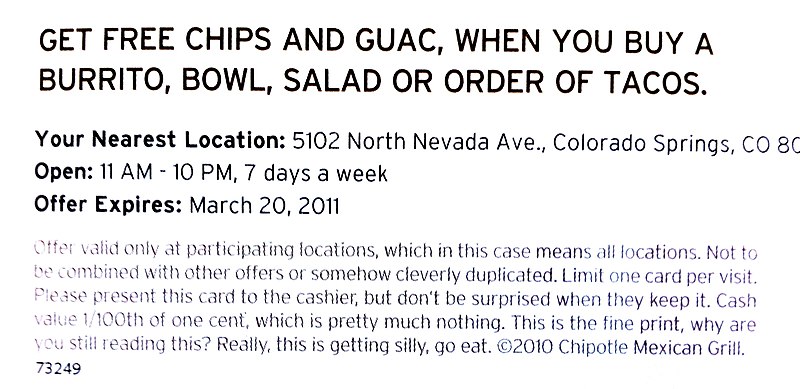

If you visit the Wikipedia entry for “fine print,” you’ll see the image above as an example. Fine print — basically, noticeably smaller words on a document — is typically used to disclose all the legalese without diverting the consumer’s attention from the important part. The image above is a great example for two reasons. First, it demonstrates the dichotomy well: “free chips and guac” is the message you want the consumer to take away from the card, and stuff like “cash value 1/100th of one cent” is something that the lawyers made the marketers include, but the consumer doesn’t really care about. (You, a fan of trivia, probably want to know what that’s about, though. Good news: today’s “From the Archives” link explains it.) And second, the image makes a tongue-in-cheek joke about the fact that no one ever reads the fine print, stating “this is the fine print, why are you still reading this?” before suggesting the consumer go eat already.

It’s true — people almost never read the fine print.

That is why a Georgia high school teacher named Donelan Andrews is $9,546 richer.

In 2019, Andrews was planning a trip to England with some friends but realized that there was a reasonably high chance that they’d have to cancel last minute. As the Washington Post reported, “each had someone in their lives who were elderly or sick,” so Andrews decided to invest in some travel insurance. She did a bit of Googling and discovered a company called Squaremouth which had what she was looking for: a policy, called “Tin Leg,” that would reimburse her if she did not take the trip. The policy cost her $454.

Like any other insurance company, though, Squaremouth won’t take your money unless you agree to what often feels like an endless stream of terms and conditions that most lawyers probably can’t understand. While Squaremouth wants you to be aware of what you’re agreeing to, they also know that almost no one reads the fine print. And who can blame us? Per the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the policy Andrews agreed to was more than 4,000 words long, or about eight times the length of the email you’re now reading. But buried on page 7, per the AJC, was a magic paragraph, pasted below:

In an effort to highlight the importance of reviewing policy documents, we launched Pays to Read, a contest that rewards the individual who reads their policy information from start to finish. If you are reading this within the contest period … and are the first to contact us, you may be awarded the Pays to Read contest Grand Prize of ten thousand dollars.

Andrews was used to reading the fine print, though. As reported by USA Today, she told Squaremouth that “she never skips fine print and that she tells students in her life skills classes to do the same. ‘I used to put a question like that midway through an exam, saying ‘If you’re reading this, skip the next question,’ she told the company. ‘That caught my eye and intrigued me to keep reading.'” So she claimed the prize — and received the full $10,000. (She still bought the $454 insurance policy, so I figure it nets to $9,546, in case you want to check my math.)

Squaremouth was happy to pay up. In fact, according to the Washington Post, they made some charitable donations in Andrews’ honor as well: “5,000 each to the two Georgia schools Andrews works for — Upson-Lee High School and Lamar County High School — as well as another $10,000 to Reading Is Fundamental, a children’s literacy charity.”

Andrews told the AJC she was going to use some of the money to take a trip to Scotland to celebrate her anniversary. It went unreported whether she purchased travel insurance for that trip (possibly) or if it netted her another $10,000 (doubtful).

Bonus fact: If you signed up for free public WiFi in London’s business district in 2014, you probably should have also read the fine print — because you may have agreed to give up a child. As the Guardian reported, in June of that year, researchers “backed by European law enforcement agency Europol” set up a hotspot that offered passersby free Internet access, but the terms and conditions included a clause stating that “the recipient agreed to assign their first born child to us for the duration of eternity.” Six people agreed to the terms but they don’t have to worry; the security firm didn’t think the clause was enforceable (and wasn’t really interested in your kids anyway).

From the Archives: Why Do Coupons Have a Cash Value of a Fraction of a Cent?: As promised above.