The Bad Reason It’s Not Treason

If you were an American during the Revolutionary War, there was a very simple rule: don’t go and fight for the British. If you were caught, it would likely be the last thing you did: serving the enemy was treason, and in most states, the penalty for treason was death. That was certainly the case in Virginia; the law at the time — which is still in effect today, with some updates — defined treason as giving “aid and comfort” to the enemy, “if proved by the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or by confession in court” was a felony. Today, it is punishable by life imprisonment, but at the time, the state could — and did — execute those found guilty, often by hanging.

On April 2, 1781, a man named Billy was tried for treason by a Virginia court. The allegations were simple: he was accused of leaving Virginia and joining the crew of a British warship. Billy claimed he was brought to the ship against his will and had no intention of fighting against the American state in which he lived and that he never actually took up arms in furtherance of his alleged treason. But most of the jury disagreed, and at the time, Virginia didn’t require unanimity among jurors to find someone guilty. Billy was convicted and sentenced to death.

The two jurors who objected to Billy’s sentence — Henry Lee II and William Carr — weren’t about to give up. They didn’t necessarily doubt that Billy had joined the British, nor did they doubt that executing him for his treachery was just. They had a larger problem with the case. Billy was a slave, and to acknowledge his treason would be to tacitly endorse his status as a citizen.

So Lee and Carr argued that being a slave, Billy couldn’t commit treason — as the property of someone else, he was a non-citizen and therefore owed no obligation to a country that wasn’t his to claim. The pair wrote to Thomas Jefferson, then the governor of the state; per Encyclopedia Virginia, the pair wrote that a slave, “not being Admited to the Priviledges of a Citizen owes the State No Allegiance and that the Act declaring what shall be treason cannot be intended by the Legislature to include slaves who have neither lands or other property to forfiet.” Jefferson agreed, staying his execution.

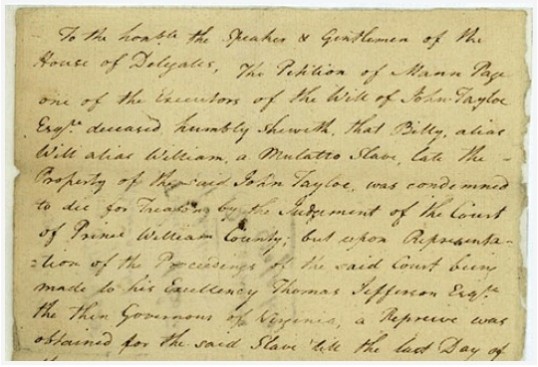

The law of the time didn’t empower the governor to pardon the convicted — that was vested in the legislature — so shortly thereafter, a member of the Virginia House of Delegates (the lower house of the state’s legislative branch) wrote the letter above to his colleagues, asking them to set Billy free entirely. The letter, pictured above via another Encyclopedia Virginia entry, reads as follows:

To the honble the Speaker & Gentlemen of the House of Delegates,

The Petition of Mann Page one of the Executors of the Will of John Tayloe Esqr deceased, humbly sheweth, that Billy, alias Will alias William, a Mulatto Slave, late the Property of the said John Tayloe, was condemned to die for Treason by the Judgment of the Court of Prince William County; but upon Representation of the Proceedings of the said Court being made to his Excellency Thomas Jefferson Esqr the then Governour of Virginia, a Repreive was obtained for the said Slave ’till the last Day of the present Month. Your Petitioner sensible that a Pardon for Treason can only be obtaine granted by the Legislature, begs that he may be heard before a Committee on Behalf of the said Slave.

Mann’s petition was successful; Billy was freed from his sentence, as the Virginia government would rather let a traitor live than acknowledge that he was more than someone else property. Assumedly, though, he was not freed from being a slave. His fate, much like his last name (if he had one), was not recorded by history.

Bonus fact: The most famous American traitor is probably Benedict Arnold. But before Arnold turned to join the British, he was an accomplished major general on the American side in the Revolution, leading troops to victory in the Battles of Saratoga. If you go to Saratoga today, you’ll find the Boot Memorial, attesting to his triumphs there. The inscription tells the story of how he was “the ‘most brilliant soldier’ of the Continental Army who was desperately wounded” at Saratoga, yet, in the second battle there, was credited with “winning for his countrymen the decisive battle of the American Revolution.” What you won’t see on the Memorial is Arnold’s name — due to his treason, the identity of the “most brilliant soldier” is omitted.

Double bonus!: Henry Lee II, who co-wrote the petition to Jefferson in the main story above, was the grandfather of Robert E. Lee, the leader of the Confederate army in the American Civil War.

From the Archives: Fredrick Douglass Is Not Amused: Why the famed former slave never smiled (in pictures, at least).