The Counterintuitive Problem of Dry Counties

In the late 1800s and into the 20th century, the temperance movement — that is, an organized effort to ban alcohol consumption — found a significant foothold throughout the U.S. and throughout much of the Western world. In the U.S. specifically, those efforts — legislatively, at least — found success; from 1920 to 1933, there was a nationwide prohibition on the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. But that wasn’t the only time booze was banned in parts of the United States. Before the period known as Prohibition, many states and local governments instituted similar bans. Some are still on the books today.

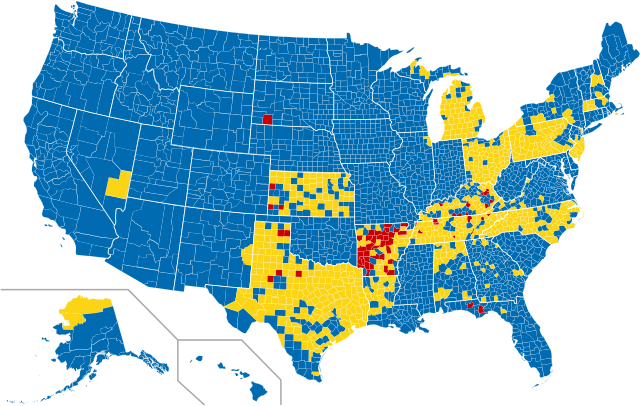

Let’s start with a map.

The map above comes from the Wikipedia entry for “dry county,” which the online encyclopedia’s editors define as “a county whose government forbids the sale of any kind of alcoholic beverages.” The yellow counties have some meaningful restrictions on such sales; the red ones ban alcohol sales entirely. (The blue ones do not have any significant restrictions beyond age requirements, although it’s inaccurate to say that alcohol is fully unregulated in those areas; for example, in New York State, you can’t buy wine in a grocery store.) While most of those bans date back a century and, historically, were passed because of a moral objection to drinking altogether, there may be a good reason to keep those bans on the books, at least theoretically. to prevent car accidents. Driving under the influence of alcohol (“DUI”) is unfortunately very common throughout the United States, and it all too often leads to tragic results. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, “about 31% of all traffic crash fatalities in the United States involve drunk drivers. In 2021, there were 13,384 people killed in these preventable crashes.” In theory, banning the sale of alcohol locally could help stem that tide.

But there’s a problem with that. In 2003, a team of researchers looked into the nearly 40,000 alcohol-related crashes on state roads in Kentucky. (As the map above shows, Kentucky has a lot of yellow counties with a few red ones mixed in.) The researchers found that local booze bans didn’t stop DUI accidents from occurring at all, and may have made them more common. Per the paper, “a similar proportion of crashes in wet and dry counties are alcohol-related but that a higher proportion of dry counties residents are involved in an alcohol-related crash.” The paper’s authors concluded that “circumstantial evidence that some dry county drivers may be driving to wet counties to consume alcohol thus increasing impaired driving exposure.”

Unfortunately, the bad news didn’t stop there. Not only might there be an uptick in DUIs in dry counties, but those DUIs are more likely to end in fatalities. As the American Addiction Centers website explains, “since dry towns are in rural counties, there are not many options for taxis or public transportation, especially late at night; when people drive to get drunk, they have to drive vast distances, and they drive back while dangerously intoxicated.” That theory is borne out by the data; per the same website, “Figures from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration found that people in the state’s dry counties had a fatality rate in alcohol-related accidents of 6.8 per 10,000 people over five years, which was more than three times higher than the rate in the state’s wet counties: 1.9 per 10,000 people. The less distance people have to drive to get their alcohol, the less likely a driving under the influence fatality is.”

And the data gets even worse when you look past drinking. In 2015, researchers at the University of Louisville looked into methamphetamine use in Kentucky, and the numbers don’t look great for the alcohol-free counties. As the Washington Post summarizes, the research team “noticed that dry counties had higher rates of meth lab busts, as well as higher rates of meth crimes overall.” Per the Post, the research concluded that “people who buy alcohol in places where it’s illegal become accustomed to dealing with the black market,” and therefore have less of a barrier to buying illegal drugs, too. Per the study, “if all counties were to become wet, the total number of meth lab seizures in Kentucky would decline by about 25 percent.”

The good news is that local governments and the electorate are taking heed of this data — or, at least, want to be able to drink without having to skirt the law (or travel far). In May 2023, voters in six Kentucky counties were faced with ballot measures that would allow the sale of alcohol within their borders, and four of those counties voted to allow at least some such sales.

Bonus fact: Moore County, Tennessee, is a dry county, with one small exception. The county seat of Moore is Lynchburg, which is home to the distillery of whiskey company Jack Daniel’s. The ban on selling alcohol doesn’t extend to the production of booze, so that’s perfectly, fine, but you can’t buy their product anywhere nearby. The exception? In 1994, the state government passed a law that superseded local regulations and allowed the distillery’s gift shop to sell “commemorative decanters” of their Tennesee Whiskey.

From the Archives: The Prohibition Prescription: Wanted to buy alcohol during Prohibition? All you needed was a doctor’s note.