The Prohibition Prescription

As of July 1 of this year, 18 of the 50 United States have a law on the books allowing for the medicinal use of marijuana. To many, it’s just good policy — if a drug can help people suffering from cancer treatments or glaucoma, we should allow for it. For others, such as New York City mayor Mike Bloomberg, it’s “one of the greatest hoaxes of all time,” and similarly others see it as a trojan horse which will lead to widespread legalization. But regardless of one’s opinion on the matter, there’s one thing that’s for sure: the idea of providing a medical exception to a banned drug is not novel.

Just ask Walgreens.

Walgreens is the largest pharmacy chain in the United States, with over 8,000 stores. There’s at least one Walgreens in each of the 50 states, D.C., Puerto Rico, and Guam. The company, founded by a man named Charles Walgreen, Sr., got its start in 1901 in Chicago. By 1919, there were 20 Walgreens stores in the city. About ten years later, in 1930, there were between 350 and 550 across the United States, depending on the source one goes by. To a large degree, Prohibition was the reason why.

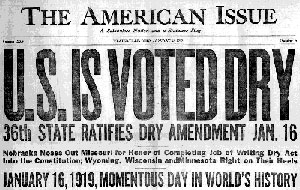

In 1919, the United States ratified the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, which barred alcohol and empowered Congress to create legislation to enforce that edict. In 1920, the Volstead Act, promulgated in 1920, did exactly that. But the Volstead Act had some exceptions. The full text of the Act is available here, but pay particular attention to Section 6, which read in part:

No one shall manufacture, sell, purchase, transport, or prescribe any liquor without first obtaining a permit from the commissioner so to do, except that a person may, without a permit, purchase and use liquor for medicinal purposes when prescribed by a physician as herein provided.

Basically: the doctor could write you a script for some booze. You just needed to take that note to a pharmacy and you could get yourself some medicinal whiskey. And guess what Walgreens started selling?

Milkshakes!

According to historian Daniel Okrent, in his book “Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition,” that’s what Walgreens’ family historians ascribed to the massive growth of their business. Okrent, not being on the company dime, takes a more skeptical tone:

In 1922, Walgreens introduced the milk shake, which family historians have credited with the chain’s next growth spurt. But it’s doubtful that milk shakes alone were responsible for Walgreens rocketing expansion from 20 stores to an astonishing 525 during the 1920s. Something Charles Walgreen Jr. told an interviewer many years later suggest another possibility. The elder Walgreen worried about fire breaking out in his stores, his son recalled, but this apprehension transcended concern for his employees: he “wanted the fire department to get in as fast as possible and get out as fast as possible,” Charles Jr. remembered, “because whenever they came in we’d always lose a case of liquor from the back.

The New York Times buttresses this claim. In an article discussing medicinal marijuana (unsurprisingly), the Grey Lady noted that Walgreens was the big winner:

During America’s dry age, the federal alcohol ban carved out an exemption for medicinal use, and doctors nationwide suddenly discovered they could bolster their incomes by writing liquor prescriptions. Pharmacies, which filled those prescriptions, and were one of the few places whiskey could be bought legally, raked it in. Through the 1920s, the number of Walgreens stores soared from 20 to nearly 400.

But one thing has changed: in most cases, one can no longer buy whiskey at Walgreens.

Bonus fact: Okrent’s book reveals another way to avoid Prohibition’s reach — this one employed by Herbert Hoover, then the U.S. Secretary of Commerce (and later, President of the United States). Foreign embassies, while within the borders of the United States and in many cases, within Washington, D.C., were and are considered to be part of the countries which they represent. Hoover, per Okrent, developed a Prohibition ritual which took advantage of this loophole — on the way home from work, he’d stop by the Belgian embassy for a drink.

From the Archives: Liquor, Sicker: A dark, morbid way the U.S. enforced the Volstead Act.

Related: “Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition,” by Daniel Okrent, as noted above. 169 reviews, 4.3 stars. Available on Kindle.