The Font That Toppled a Government

Nawaz Sharif was Pakistan’s Prime Minister three times — from late 1990 until July 1993, then from February 1997 into the fall of 1999, and finally again from June 2013 until his ouster in July 2017. Currently, he’s in prison — and Calibri is partially responsible for that.

What’s Calibri? It’s the font represented in the image above. You’ve almost certainly seen it before — if you open up a current version of Microsoft Word or Outlook, it’s the default font unless you or someone else have changed your settings, replacing the long-standing go-to Times New Roman a bit more than a decade ago. That’s because it’s supposedly more readable — which is, really, the point of a typeface anyway. But for Sharif, it was his undoing.

Pakistani politics are complicated — the fact that the same guy could serve three non-consecutive terms leading the government (and with non-standard term lengths each time) should be enough evidence of that. In Sharif’s case, though, it’s even more complex. The first time he left office, it was because Pakistan’s President, at the time, had the power to dissolve the elected governments unilaterally, and that’s exactly what happened. The second time Sharif was in office, he was ousted by a coup, then jailed and exiled. He returned in 2007 only to be immediately deported, then returned again a few months later. A few years after that, his party won enough seats in the National Assembly to lead a coalition government, one which put Sharif back in the prime minister’s role. Whether he was successful during that third term is a conversation for another newsletter. But how that term ended, well, let’s dive in.

In 2015, a whistleblower — who to this day remains anonymous — leaked a collection of 11.5 million documents taken from a Panamanian law firm. The documents now colloquially called the Panama Papers, were obtained by a group of reporters known as the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. In April 2016, the ICIJ reported on the leak for the first time and did so in grand fashion by publishing an in-depth analysis of the documents. The investigation, available here, showed that the law firm had set up more than 200,000 offshore accounts and shell companies on behalf of some of the world’s richest and most powerful people. While the existence of these offshore entities isn’t, in and of itself, unlawful, it’s likely that many of them were being used for unlawful or unethical purposes, such as tax evasion or money laundering. And the Sharif family was among those named.

Specifically, per the BBC, “the Panama Papers leaks linked [Sharif’s] children to offshore companies used to buy London flats,” putting into question why Sharif hid these properties from the Pakistani people. This prompted a probe of Sharif’s finances, and, as NPR reported, justified a long-standing belief among “the country’s citizens that the ruling class [was] corrupt.” Sharif claimed that there was nothing nefarious about his family’s interest in the London apartments — they were rich and they bought property, no big deal — but those skeptical of him (and his political opponents) didn’t believe him. Of particular problem was that Sharif’s daughter, Maryam, was specifically named as owning some of the apartments. Because her father, the prime minister, had claimed her as a dependant, he was supposed to disclose her (and by extension) his financial interest in such high-end property.

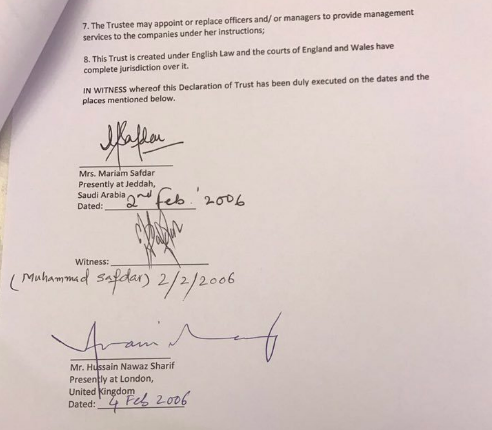

But Maryam had an excuse — the Panama Papers, she claimed, got a key detail wrong. She wasn’t the owner of her apartment at all. Rather, she was merely a trustee with no actual ownership interest, and the beneficiary of the apartment was her brother. In November of 2016, she tweeted out images of legal documents purporting to prove just that. Here’s a screenshot of the signature page from that document.

Maryam Nawaz Sharif, listed as Mariam Safdar in the document, is the trustee, and the document quite clearly states it was signed in February of 2006 when her father was living as an exile in London. But that 2006 date? That was the Sharif family’s fatal mistake. The font used in the document is Calibri, and it wasn’t added to the commercial version of Microsoft Word until 2007.

Oops.

The Pakistani court, the Globe and Mail reported, took note of this time-traveling font and ruled that the “document is fake, fabricated and not worthy of any reliance.” For Sharif, this was a big problem; per the Globe and Mail, “in his mandated asset declarations, he had listed [his daughter] as a dependent but had not disclosed the London penthouses.” Basically, the court concluded, Sharif had been hiding assets for some reason or another, and his dishonesty disqualified him from holding office. The ruling also referred Sharif to the criminal court to see if corruption charges were in order — while he attributed his family’s wealth to his family’s steel and sugar businesses, there was evidence that ill-gotten loans, gifts, and business deals (i.e. political graft) made up a significant amount of the Sharif largess.

Ultimately, the criminal court found him guilty; Sharif is now in jail serving a ten-year sentence. Next time, he’ll use Times New Roman.

Bonus fact: In 1500, an Italian publisher named Aldus Manutius came up with an idea — a printing press that used a font that resembled actual handwriting. The cursive script was more compact than typical fonts used by printers, allowing Manutius to create books that were physically smaller than his competitors. The font was widely imitated and became known as the Italian style, or “italic” for short — which is why, today, we use the word “italics” to describe slanted, often compressed text.

From the Archives: An Inkling for Ink: Why you might want to use Century Gothic instead of Calibri.