The Pearly History Behind Chinese Takeout Boxes

Pictured above is a generic Chinese food takeout box. Inside you’ll find lo mein, fried rice, chop suey, or one of many other dishes typically found at Chinese restaurants in the United States. They’re rather efficient at transporting food — they’re cheap, they do a good job keeping whatever you ordered warm, and can even unfold into a plate if need be. In fact, they’re so good at what they do, it’s a surprise that only Chinese places use them; you’ll rarely (but yes, sometimes) find Mexican or Italian or other non-Chinese food restaurants employ them.

But there’s nothing Chinese — at least, not in the “invented in China” sense — about Chinese food boxes. In fact, they’re a product of New York City. Oh, and they were made for oysters.

Today, you probably don’t associate New York City and oysters. But turn back the clock and you’ll find oysters everywhere. As Atlas Obscura explains, “oysters thrived for millennia in the brackish waters around New York Harbor, keeping the estuary clean thanks to their natural filtration abilities, and serving as a favored food for the Lenape people who once lived there. When Henry Hudson arrived in 1609, there were some 350 square miles of oyster reefs in the waters around what is today the New York metro area, containing nearly half of the world’s oyster population.” Oyster shells became a sizeable litter problem, and one oyster midden — basically a dump filled with oyster shells — turned into infrastructure; per the New York Public Library, “Pearl Street, once a waterfront road, was named for a midden and later even paved with oyster shells.” (Unfortunately for those interested in pearls, New York oysters don’t make them.)

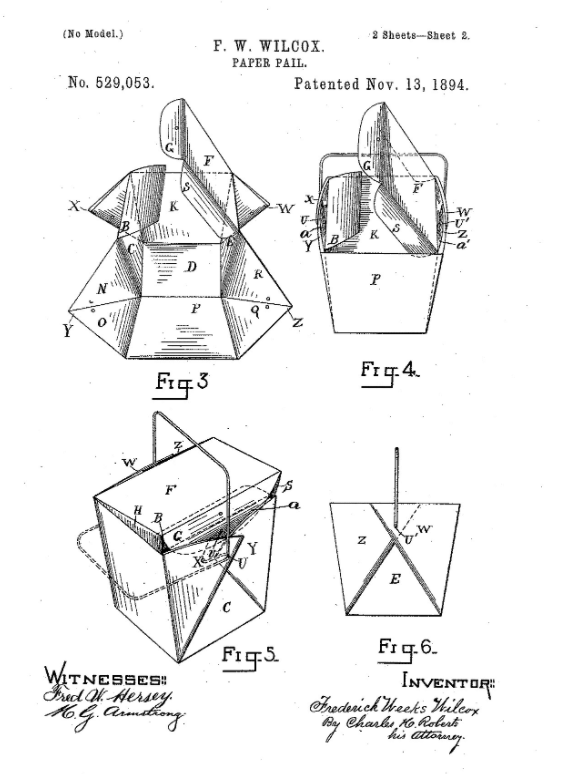

But as the oyster business grew, oyster merchants needed a way to get their product to more and more people around the city. And it turns out, transporting them isn’t so easy. According to The Dieline, “once shucked, [oysters] don’t stay fresh for very long, a more pressing concern before widespread refrigeration.” Enter “the oyster pail,” “an inexpensive, watertight package that can safely carry oysters home,” while also allowing steam to escape. Here’s an image from the patent application filed in 1894, and you’ll see it, it looks very familiar to anyone who ordered some General Tso’s chicken recently.

Today, you’re not getting oysters this way, especially not in New York. The waterways around Manhattan fell victim to overharvesting of oysters and, of course, pollution — you probably couldn’t get a customer to eat an oyster out of the East River today if you paid them. Per the New York Public Library, “in 1927, the last of the New York oyster beds was closed, primarily because of toxicity,” and while oyster bars still opened afterward, “they weren’t serving local oysters.” And that spelled bad news for the oyster pail.

But as oysters faded from the local menus, Chinese food was booming. Inexpensive, disposable containers that were leakproof were perfect for the emerging takeout business and Chinese places began adopting the containers as early as the 1920s. In the 1970s, according to the New York Times, “a graphic designer (whose name, sadly, has been lost to history) working at the company now known as Fold-Pak, put a pagoda on the side of the box and a stylized ‘Thank you’ on top. Both were printed in red, a color symbolic of good fortune in China, where oyster pails are little known.” A box intended for New York oysters had found a new purpose in life — one that endures today.

Bonus fact: You won’t find a lot of American “Chinese” foods in China, but one you may find — kind of — is chop suey. But only kind of. In the United States, chop suey is basically a stir fry of various vegetables — Epicurious suggests using “celery, mushrooms, bok choy, bamboo, and water chestnuts” with pork, but notes that “you should feel free to use whatever veggies or meat you have lurking in the fridge.” And that comports with the dish’s likely origins, and why you can find it in China: per Food & Wine, there’s a good chance that “Chinese Americans invented the dish based on tsap seui, a Cantonese dish that translates to ‘miscellaneous leftovers.'”

From the Archives: The Luckiest Dessert in History: A story about fortune cookies, which, by the way, aren’t traditionally Chinese either.