The Plague Village

Starting in about 1347, the bubonic plague started a pandemic called the “Black Death.” The strain of plague-causing bacteria dated back to China from a few decades prior, but no one knows where it began, exactly. Because it kills virtually everyone who comes in contact with an infected person, we know where it went — all throughout Europe, China, and into Africa. In total, the Black Death claimed, roughly, the lives of half of China’s population, a third of Europe’s, and 15% of Africa’s.

The disease most likely was not spread from person to person directly. Rather, it is now believed that the plague was carried by rats, typically, and then transmitted to people via bites from infected fleas. Only when the fleas died out — typically, when winter hit — did the plague ebb. At other times, it spread rapidly, causing a massive death toll.

Three centuries after the Black Death pandemic, the plague returned to central England to a village called Eyam. (Its pronunciation rhymes with “team.”) In late August or early September of 1665, a tailor named George Viccars imported some cloth from London. Unfortunately, the cloth was infested with fleas. Within a week, Viccars was dead — and the village was doomed to follow in his footsteps.

Enter William Mompesson, the town rector. Mompesson, per PBS, convinced his fellow townsfolk to self-quarantine, making the likely death sentence a near certainty — but preventing the plague from spreading throughout England. Almost everyone in the town was exposed to the plague-bearing fleas and the disease held firm in Eyam for about 14 months. And in the end, something amazing happened: the plague abated and about 25 to 50% of the town, somehow, survived.

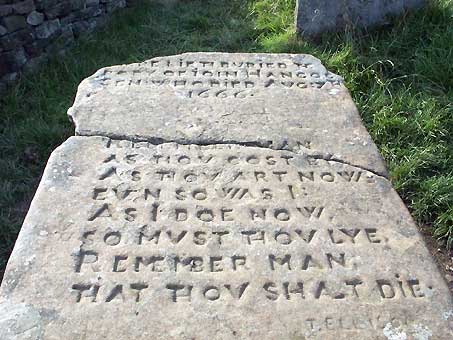

Flea avoidance was not the reason why, either. At least two survivors were almost certainly exposed to the disease. A woman named Elizabeth Hancock buried her husband and six children all within an eight day period (one at the grave marked by the stone pictured above), and yet, she did not contract the plague. Similarly, Marshall Howe, the town’s unofficial gravedigger who buried many corpses, somehow survived. How they did so is unknown, but there are some camps which believe that a genetic mutation which affects about 1% of the population of present-day Europeans may be why. The mutation is believed to affect the human immune system — strangely, in a positive way. The mutated gene may have prevented the survivors’ white blood cells from becoming infected with the plague bacteria, and therefore, kept these people alive.

Bonus fact: The gene cited above is the CCR5 gene and the mutation is called Delta 32. The Delta 32 mutation may also provide HIV resistance. In 2010, New Scientist reported on the case of an AIDS patient who underwent intensive chemotherapy followed by a bone marrow transplant to treat leukemia. The donor had the Delta 32 mutation, and that mutation carried over into the recipient. Afterward, the marrow was also able to resist HIV.

From the Archives: Pellagra: A terrible disease which, like the plague, was believed to be caused in part by unclean conditions.

Related: A book on the Eyam plague from 1842.

Leave a comment