The World Record That Will Definitely Stick

On August 7, 2021, Indian athlete Neeraj Chopra took the field at Japan National Stadium, representing his country in the pandemic-delayed 2020 Summer Olympics. When he left the stadium, he did so a champion — Chopra’s second attempt at the javelin throw went 87.58 meters, enough to take gold by nearly a full meter. His coach at the time, Uwe Hohn, was probably very proud of him; Chopra’s medal was the first ever gold earned by a track and field competitor for India.

Had Chopra taken the exact same javelin and traveled back in time to compete against his coach during his coach’s heyday, Chopra would have lost — by a lot. Uwe Hohn is the man behind the longest javelin throw ever on record — 104.80 meters, all the way back in 1984 — and it’s incredibly unlikely that Chopra, or anyone else, will ever break that mark.

But don’t blame Chopra. It’s not his fault. Blame the javelin.

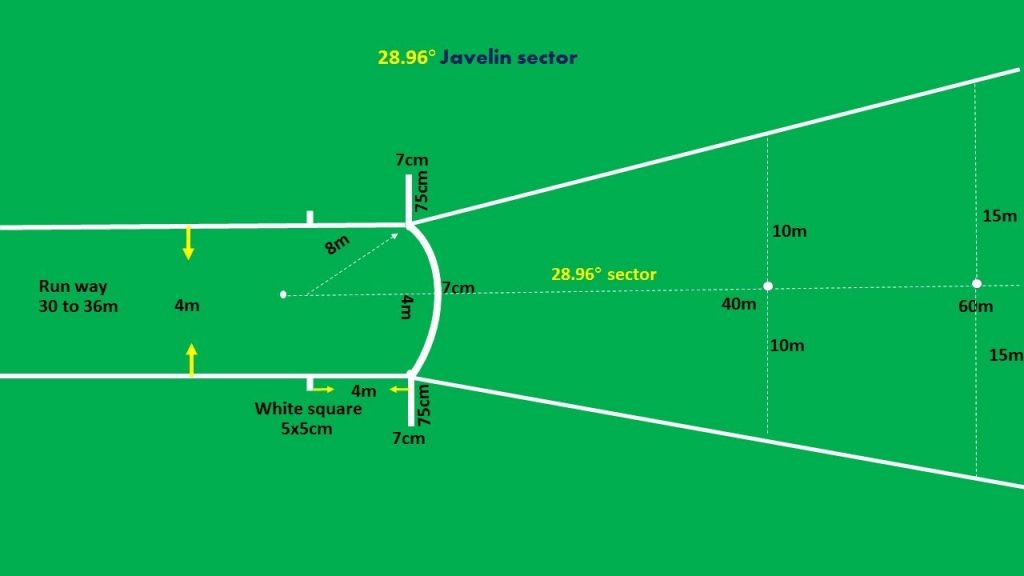

If you’re not familiar with the sport of javelin throwing, it’s pretty simple. Competitors have a javelin — a really long stick — in their hands, typically with a pointed end. One by one, they grab their stick, take a running start, and then throw the javelin as far as they can, within the two white lines as seen in the diagram above. Provided that the competitor doesn’t run too far forward (crossing that bulging white line in the middle of the image above) and the javelin lands point first and in-bounds, the throw is legal. The competitor who throws the javelin the furthest wins.

Like most other Olympic sports, we tend to see world records fall every few years. Athletes get faster and stronger, techniques become more refined, and technology improves. And for decades, javelin throwing was no exception. For the sport’s first 70 years as an Olympic event, the world record fell more than 30 times.

Unfortunately, as throws got longer, they also became controversial. Over time, javelin throwers and manufacturers changed their approach to the sport; instead of aiming for a high launch angle and long arch, they focused on throws that stayed more parallel to the ground in hopes of increasing the total throw distance. But this caused a problem in judging the outcomes of the throw. For a javelin throw to be legal, the front has to land first. And sometimes, it’s hard to tell what part of the javelin touched the ground first. As The Centre for Sports Engineering Research explains, “there was an increasing amount of times when the javelin would land flat on the ground, resulting in heated protests when these throws were declared invalid by the competition officials.” Starting in the early 1980s, the International Amateur Athletic Federation discussed changing the javelin’s acceptable design parameters to prevent these flat landings.

But before the IAAF could act, the javelin became downright dangerous. Hohn’s 104.80-meter throw was the first to break the 100-meter barrier, and that caused a safety concern. An errant throw at that distance could easily make its way into the crowd, spearing an innocent bystander who is hoping to get close to the competition, but not that close. So in 1986, the IAAF introduced new rules requiring a number of changes to the javelin — changing its center of gravity and, ultimately, making it much harder to throw such long distances.

As a result, Uwe Hohn’s world record is probably unapproachable. And that’s not great for competition, so officially, it’s no longer the world record that javelin throwers aim for. The IAAF reset the records in 1986, only counting throws made by throwers using now-legal javelins. A Czech athlete named Jan Železný now holds the record at 98.48 meters, and that make has stood for more than 26 years. It’s unlikely if anyone will ever come close to matching Hohn’s mark.

Bonus fact: Uwe Hohn’s record is still an official one, but Jan Železný’s first world record was rescinded — and again, not through any fault of his own. In 1990, some throwers, including Železný, began using a javelin with a serrated tail, which was legal at the time but ended up effectively reversing the changes made under the 1986 javelin modification requirements. In July of 1990, Železný used one of these serrated javelins to break the UK’s Steve Backley’s record (which Backley had set just 12 days prior using a non-serrated javelin); six days after that, Backley took back his record, using a serrated javelin. The IAAF outlawed serrated javelins the next year and rescinded both Železný’s and Backley’s throws (and two others by Finland’s Seppo Räty). Železný, using a non-serrated javelin, finally took the record from Backley in 1993 and broke his own record twice thereafter.

From the Archives: Eric the Eel: An unlikely Olympian.