Treemail

In the 1971 book The Lorax, the incomparable Dr. Seuss tells the story of an environmentally-conscious monster (the Lorax) and its efforts to protect Truffula trees (a fictional species) from an industrialist named the Once-ler who is chopping them down. The story is meant as a parable, teaching children the importance of conservation, and notes that the trees can’t advocate for themselves, so others have to. The Lorax, being the protagonist, is that advocate; he tells the Once-ler that he “speaks for the trees, for the trees have no tongues.” It’s a nice story, even though both the Lorax (who doesn’t think any trees should be turned into useful items called Thneeds) and the Once-ler (who wants to cut down all the Truffulas) are extremists who apparently forgot that trees are renewable resources if you just plant a lot more of them.

But either way, trees are nice to have around. They’re pretty resilient, too, but some events — most notably Once-lers and droughts — can wreak havoc on their populations. To combat the Once-lers, we have Loraxes. To combat droughts, we have …. well, if you’re the Australian city of Melbourne, you have the Urban Forest team.

Melbourne isn’t a rural, wooded area — it’s the second most populous city in Australia and has a population density of 1,100 people per square mile (430 per km^2). The trees in Melbourne are in city parks and, more importantly for our purposes, run alongside streets. In 2009, per the BBC, the city was home to 77,000 trees, but due to drought, an estimated 40% of them were “struggling or dying.” The city wanted to reverse that, and dedicated resources to plant 3,000 new trees a year. But there was more to be done. If the city could identify those trees which were damaged but not past the point of doomed, that’d be great, right? Unfortunately, with 77,000 trees, finding the ones that can be saved is difficult at best, and, unfortunately — as the Lorax tells us — the trees have no tongues, and can’t quite yell for help.

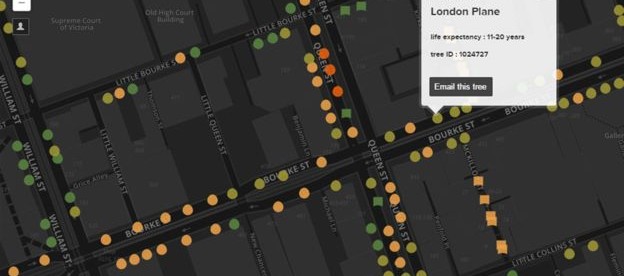

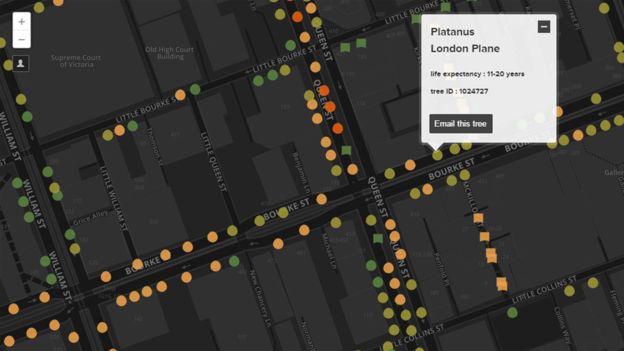

Melbourne came up with a solution for this problem in 2013. Called the “Urban Forest Visual,” it’s a website (available at that link) which catalogues all the trees and assigns each one an ID number. If a passerby notices that a tree is in distress, he or she can log onto the website, find the tree on a map, and send a note to city officials alerting them to the problem. All you need to do is click the button (as seen in a screenshot I took from the BBC, below) which reads “Email this tree.”

And now, people can be the Lorax, and speak for the trees.

But that’s not all they’re doing. People are also speaking to the trees.

The “email this tree” button means “email the city about this tree” — or, at least, that’s what it was intended to express. But that’s not actually what it says, and many people have interpreted the language to mean “send an email to this tree.” That’s a bit weird, because not only do trees not have tongues, but they also do not have eyes or iPhones (although some have other apple products) and therefore can’t read the email. But one can appreciate the symbolism just the same. From the Urban Forest Visual’s launch two years ago through July of this year, the trees have received roughly 3,000 emails, according to ABC News (Australia). The most emailed tree, per ABC, is a golden elm (ID 1028612) on Punt Road, on the corner of Alexandra Avenue and “across the road from the Yarra River,” you know the area. The tree is so popular that at times, the Urban Forest team will reply back on its behalf. (They type for the trees, for the trees have no fingers.)

So, what does one email a tree about? Anything and everything. Here’s one example, below (via the BBC), but there have also been emails about cricket, exam anxiety, and even the Greek debt crisis.

Weeping Myrtle, Tree ID 1494392

5 July 2015

Hello Weeping Myrtle,

I’m sitting inside near you and I noticed on the urban tree map you don’t have many friends nearby. I think that’s sad so I want you to know I’m thinking of you. I also want to thank you for providing oxygen for us to breath in the hustle and bustle of the city.

Best Regards, N

If you’d like to read more of the emails, both the BBC and ABC links above have examples, as do the Atlantic, here, and News.com.au, here.

Bonus Fact: The original version of The Lorax made a reference to the polluted waters of Lake Erie. But a decade or so later, the waters had been mostly rehabilitated, and Erie was no longer as “smeary” as it had been when Seuss had originally written his book. Members of the rehabilitation team asked Dr. Seuss to update the book to reflect the change, and he did. Starting in 1986, editions of the book omit the reference to the lake. A side-by-side comparison of the relevant page from the two editions can be seen here.

From the Archives: A Tree Falls in North Korea: A special operations mission to cut down a tree.

Take the Quiz: Name all the words in Dr. Seuss’ classic book Green Eggs and Ham.

Related: The Lorax.