Why Aluminum Foil Has a Shiny Side and a Not-Shiny Side

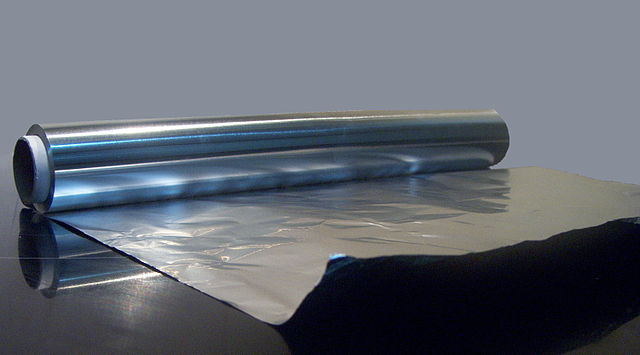

Pictured above is a roll of aluminum foil. If you’re outside the U.S. or Canada, you probably call it “aluminium foil,” and that’s a story for another day. You may also call it “tin foil,” which is a misnomer, and also a story for another day. Whatever you call it, aluminum foil is very useful, particularly when cooking — it’s oven-safe but cools very quickly when removed from the heat source, so you’re probably using it to cover your casseroles or as a liner for a baking sheet. In fact, you probably have some in your kitchen right now. If you do, go find some and you’ll see that the two sides of the foil are different — one is shiny and reflective, and the other isn’t. If you don’t have any foil nearby, the image above shows what I’m talking about; the foil still on the roll is very shiny but the part pulled out isn’t.

What’s going on here? The shiny/matte mix isn’t there to further some sort of advanced cooking techniques, nor is it there to prevent the government from reading your brains. Rather, it’s a byproduct of a manufacturing process designed to keep costs down.

The sheets of aluminum foil rolled up in your kitchen are very thin, similar to a sheet of paper. Per Wikipedia’s editors, “standard household foil is typically 0.016 mm (0.63 mils) thick, and heavy duty household foil is typically 0.024 mm (0.94 mils),” where a “mil” is a thousandth of an inch. Getting the foil that thin makes it very malleable but without making it likely to break in normal use. But the manufacturing process itself isn’t a “normal” use — it’s a lot more intense. According to Reader’s Digest, during that process, called “milling,” the “heat and tension is applied to stretch and shape the foil” into the long, pristine sheets we’re used to.

And during that process, sheets of foil need to be a lot thicker than 0.016 mm; otherwise, the foil runs the risk of breaking during the process. That would ruin the product, so manufacturers came up with a simple solution — they mill two sheets of foil at the same time, one on top of the other. That causes the shiny/not-shiny dichotomy. As Mental Floss explains, “when the top of the top sheet and the bottom of the bottom sheet rub against the rollers, they get shiny. Since the bottom of the top sheet and the top of the bottom sheet only touch each other, they stay dull.”

For consumers, though, the difference between the two sides is cosmetic and has no impact on our recipes or the like. Today Home asked Mike Mazza, a marketing director at Reynolds Wrap, who basically said not to worry about it: “Regardless of the side, both sides do the same job cooking, freezing, and storing food. It makes no difference which side of the foil you use.”

Bonus fact: If you wanted to use a tin foil hat (well, an aluminum foil hat, but the “tin” misnomer is common in this use) to keep the government from reading your brain waves, well, that’s ridiculous. But if it weren’t ridiculous, it’d also be a bad idea. In 2008, some researchers at MIT — tongues firmly planted in cheeks — decided to see what effect tin foils hats had on invaded radio waves. And it turns out that the foil doesn’t keep the radio waves out; rather, the foil makes the radio waves more effective. The study — archived here, with lots of photos of people wearing stupid-looking foil caps — concludes that “statistical evidence suggests the use of helmets may in fact enhance the government’s invasive abilities” and wonders if “the government may, in fact, have started the helmet craze for this reason.”

From the Archives: The Battle of the Blackest Black Versus the Pinkest Pink: Apparently, this is the only other time I’ve written about aluminum foil.