Why Capital Letters are Called “Upper Case”

The first word of this sentence is a little different than the rest — it begins with a capital letter. In English, we use “upper case” letters to start sentences, identify proper nouns, and, in the Internet-age, YELL IF WE HAVE TO. (Sorry.) This isn’t something which is universal — Arabic, Hebrew, Georgian, and a handful of other languages are uincase, which is to say that there’s no such thing as upper case or lower case letters. It’s likely that Old German and Latin, English’s predecessors, were also unicase originally, but over the generations, they evolved the distinctions we use today.

But we didn’t call them “upper case” or “lower case” originally. And if you think about it, those names don’t make intuitive sense. Sure, “upper” and “lower” can kind of stand in for “larger” and “smaller, but that’s a stretch — those words really don’t actually describe the size of the letters. As for “case,” that word has nothing to do with the size of the letters at all.

So, where do “upper case” and “lower case” come from?

Printing presses.

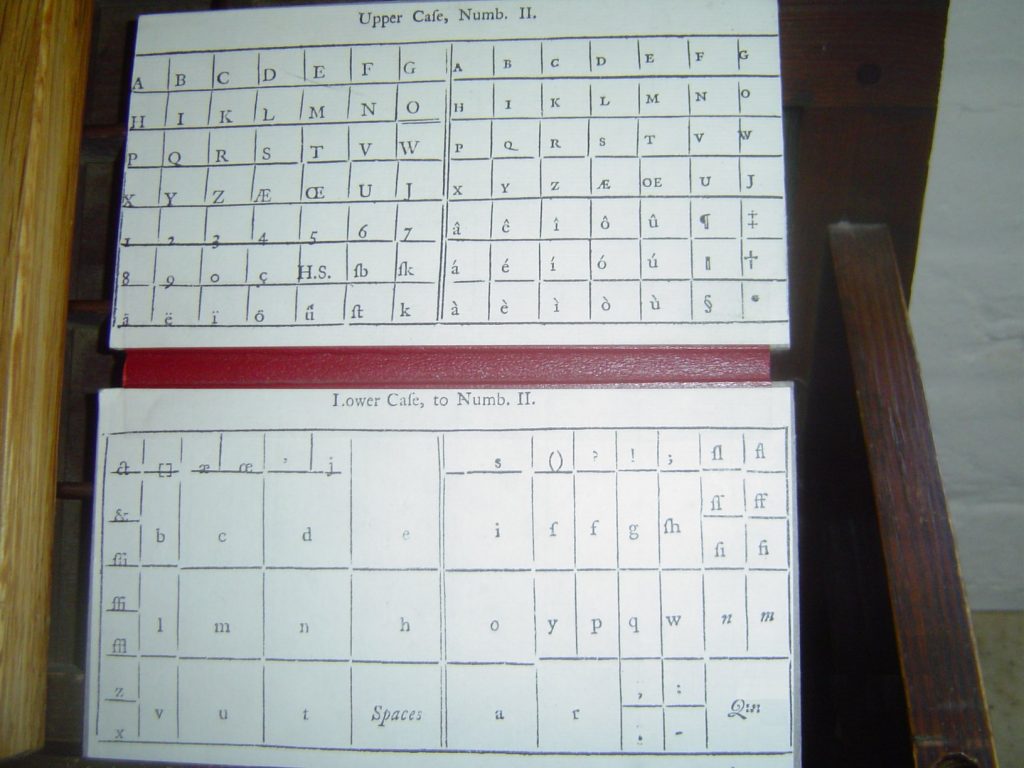

Before the advent of printing presses, “upper case” and “lower case” letters were called “majuscule” or “minuscule” letter letters, respectively, which makes some sense. Those names come from the Latin terms maiuscula littera and minuscula littera, which literally translate to “slightly larger letter” and “slightly smaller letter.” But when movable type became increasingly popular, contraptions like the below were needed.

The picture above is something called a type case. Eighteenth-century printing presses used these boxes — cases — to store little metal blocks, called “types,” which represented letters and other symbols. Each symbol had its own little rectangle, making it easy for the typesetter to find the one he needed. The typesetter would take the correct blocks from each compartment, spelling out whatever needed to be spelled out. Here’s how the compartments were typically organized:

The minuscule letters — being more commonly used, were in the more accessible bottom box — the “lower case.” The capital letters were in the top one — the “upper case.”

Over time, the alignment of the metal type within the cases evolved further; by the late 1800s, for example, typesetters used a box where the upper case letters sat to the right of the lower case ones. But by then, the new names for big and little letters had stuck.

Bonus fact: While not commonly used today, there are also upper and lower case numbers. Take a look at an older U.S. penny (or just click here) and you’ll see lower case numbers in action. In the example provided, the 9 and 7 hang below the lowest point of the 1 — that’s because those two numbers (and the 4, for that matter) are lower case.

From the Archives: Ye Olde Mispronunciation: “Ye” isn’t pronounced with the “Y” sound at the front. (It’s a typesetting thing, maybe.)