World War II’s Pre-Email E-Mail

If you’re a military service member serving abroad right now, staying in touch with your loved ones back home isn’t all that difficult. Assuming you have access to some sort of broadband service or wireless network, you can send a text, write an email, or maybe even make a video call. But all of those are relatively new. From the summer of 1942 until the fall of 1945, as many as two million American soldiers deployed to Europe to fight Nazi Germany — and they, too, wanted to stay close to those at home.

The easy and obvious solution to this problem is an archaic form of communication called “writing a letter.” (That’s a joke, please don’t yell at me.) Soldiers could — and did — find a pen and piece of paper, share their thoughts and fears with those back stateside, and drop them into a mailbox (or the equivalent). And their families and friends could do the same, just in the reverse direction.

And this caused a new problem. With so many Americans in Europe at the same time, the U.S. military was inundated with letters. Transporting millions of millions of notes from the U.S. to those stationed abroad was overwhelming; the planes bringing mail across the Atlantic were needed to bring food, arms, and other supplies as well. In other situations, the government put limits on stateside activities that hampered the war effort, and restricting letter-writing could have been a solution. But the powers that be didn’t want to go that route; they saw the mail as critical to the war effort. The National World War II Museum explains:

The critical nature of the mail effort was addressed in the 1942 Annual Report to the Postmaster General which stated: “The Post Office, War and Navy departments realize fully that frequent and rapid communication with parents, associates and other loved ones strengthens fortitude, enlivens patriotism, makes loneliness endurable and inspires to even greater devotion the men and women who are carrying on our fight far from home and from friends.”

The solution? Film.

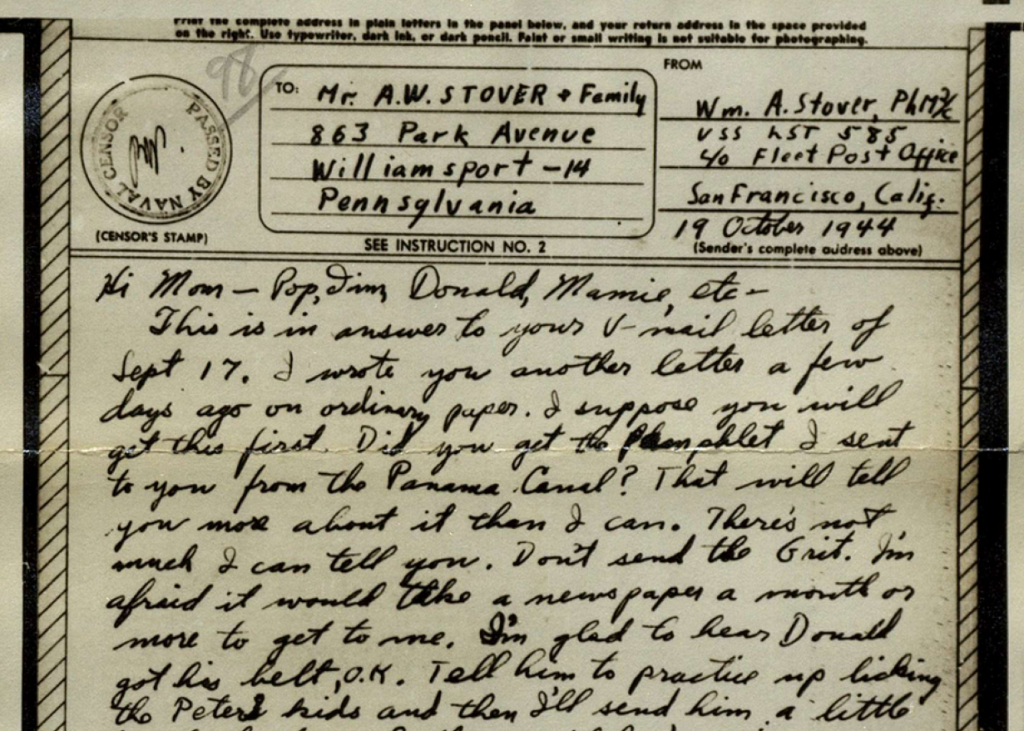

In the late 1930s and into the early 1940s, the UK partnered with the Eastman Kodak company to create something called the British Airgraph Service. Instead of transporting letters from England to fighters abroad, the Airgraph Service took pictures of the letters and stored large sets of them on one reel of film. The letters were then brought to where the soldiers were stationed, printed, and distributed. When America entered the war, they adopted a similar system and operationalized it across post offices throughout the country and to soldiers. Per the World War II Museum, V-Mail used “a standardized stationery which combined the letter and envelope into one piece of paper” that was “specially designed by the Government Printing Office and was provided free of charge by the Post Office at the rate of two sheets per person per day.”

Instead of mailing the V-mail letters, consumers brought them to their post office to be scanned by machine and recorded onto film. The film was then flown to Europe or back home; each letter was then printed and distributed as if it were the original letter, as seen above. The solution saved a huge amount of space; the United States Postal Service explained (on a Word doc, for some reason, on their website) that “roughly 1,600 letters would fit on one roll, reducing them to approximately three percent of their original weight and volume. For example, 150,000 unmicrofilmed V-Mail letters weighed 1,500 pounds and filled 22 mail sacks. When microfilmed, they weighed 45 pounds and filled one mail sack — a great space saver on crowded transports.”

V-Mail was definitely seen as inferior to “real” mail, but it proved popular nonetheless. Servicemembers weren’t charged for using it, making it an easy solution for those overseas. Back home, V-Mail was advertised as the best way to make sure that your letter made it all the way to your loved one; per the Museum, “the clerks assigned numbers to each V-mail, which corresponded to reel numbers. Each sender station kept the original copies as backups until they were notified by the receiving station that the reel had been properly transmitted.” There was, therefore, little chance of a V-mail getting permanently lost along the way. Over the course of the war, an estimated one billion V-Mail were sent and received.

Bonus fact: V-Mail’s biggest problem may have been lipstick. It was common practice at the time for letter writers to literally seal their letters with a kiss; wives and girlfriends back home would give the letters a lipstick-laden smooch to show their love to those overseas. As the World War II Museum explains, this proved problematic for the V-Mail system; “lipstick was referred to as the ‘scarlet scourge,’ because it would gum up the machines used to film the letters.” Those letters were instead sent as-is, unfilmed, to their intended recipients.

From the Archives: Space Mail: The Post Office doesn’t deliver mail into orbit or to the Moon, but mail gets there anyway. In secret.