The Cell Phone Contract Killer

There’s a good chance you’re reading these words on a mobile device such as a smartphone. If that’s the case, there’s also a very good chance that you’re paying a monthly fee to one of a handful of telecommunication companies; they, in return, provide access to their networks, beaming information (in this case, words on the screen) to your device. And to obtain that service, you probably signed a contract with them sometime in the last two years.

Hopefully, you’re happy with the service you’re getting, but maybe you’re not. In that latter case, though, there’s bad news. Depending on who your provider is — and what that contract says — you may be stuck, as many contracts have early termination fees written into them. And that fee can be in excess of $300. It’s a frustrating feature of your relationship with your service provider, especially if their network isn’t performing well.

But there’s often a way out: Die.

For good reason, mobile providers don’t want to charge an early termination fee to a recently deceased customer. While that fee isn’t going to have a meaningful impact on the company’s bottom line (and the customer won’t be using the service anyway), the fee could be a make-or-break amount to the budget of the mourning family. Atrocious news stories would certainly go viral if such a family was dinged by an uncaring cell phone provider demand it get paid for not the deceased not using its service. It’s safer to just waive the penalty.

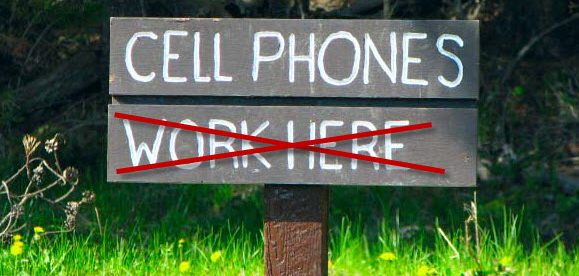

And that gave a man named Corey Taylor and idea. In 2007, Taylor, a consultant in Chicago, didn’t die. But his phones did. One cell phone after another turned out to be defective and even when they were nominally working, Verizon’s network wasn’t. No longer a fan of Verizon, he wanted out, but that came at the price of $175. As this was more than a decade ago, the phone was probably not a smartphone, and the termination fee was probably significantly more than the phone itself. He didn’t want to pay that amount, of course. And he had just read a blog post which noted that Verizon and others will waive that fee if the subscriber died.

So, he faked his own death.

He didn’t disappear and there wasn’t a funeral or anything like that. He didn’t even bother concocting a story about how he met his demise. Taylor simply created a fake death certificate and had a friend fax it over to Verizon. (Dead men don’t send faxes.) Sure, those are probably crimes — forging government documents, wire fraud, and probably a bunch of other stuff — but he probably saw early termination fees as an evil unto itself, so who cares if you break a few laws along the way? Especially because, at least initially, the scheme worked.

But alas, he didn’t get away with it. Ultimately, Verizon found out that Taylor was actually alive and well — the report doesn’t say how — and demanded its $175. He begrudgingly paid the bill and suffered no legal consequences for his attempted fraud. And he proclaimed victory regardless; Taylor told the Washington Post that “I bet I sent a definite message about how much people hate being strapped to a cellphone that doesn’t work.”

Bonus fact: Another way to get out of your cell phone contract? Try calling customer service regularly and being a royal pain in the you-know-what. As CNet reported, in June of 2007, Sprint sent a note to a small number of its customers — the big-time complainers — stating that “the number of inquiries you have made to us [over the past year] has led us to determine that we are unable to meet your current wireless needs.” As a result, the note continued, Sprint was canceling their service effective July 30th of that year. Any early termination fee was waived and any outstanding balance was zeroed out, but if the soon-to-be-former Sprint customers wanted to keep their phone numbers, they had to find another provider by the end of that July.

From the Archives: Feeling Buzzed: Ever feel like your cell phone is vibrating in your pocket even when it’s not in your pocket? You’re not alone.