When the Jazz Didn’t Stop Playing

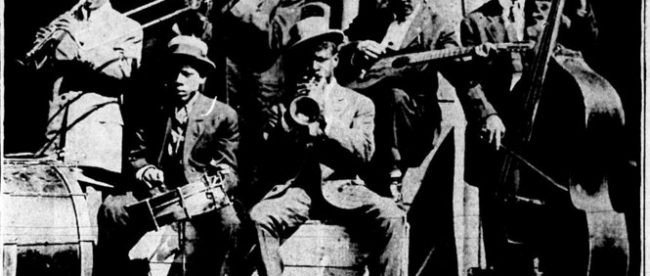

Jazz music is hard to define — it’s often improvisational with no clear path. But you know it when you hear it. Its history dates back to New Orleans as the 19th century came to a close; African-Americans in the area, just a generation removed from slavery, combined classical music with slave folk songs, creating an often eclectic musical style as a result. Today, jazz is a mainstay in its hometown — there are dozens of jazz clubs in the city known as the Big Easy. If you’re a fan of the musical style, that’s the place to be. And on the evening of Monday, March 18, 1919, one fan made sure of it.

But this isn’t a story about music. It’s a story about a murderer.

The saga begins on the night of May 22, 1918, about ten months before jazz enters the story. A couple named Joseph and Catherine Maggio were found dead in their homes, their necks slashed most likely with a razor. There was no obvious motive for the attack and the most likely suspect, Joseph’s brother, had an alibi that authorities couldn’t break. But what made this killing stand out was that the murderer, perhaps to mask the actual cause of death, had also bludgeoned the victims with an ax. A month later, two more people were attacked by an ax-wielding assailant, with one surviving. By the time March 10, 1919, rolled around, the Ax Man of New Orleans — as the otherwise unidentified murderer became known — had attacked nine people, claiming five lives.

And he wasn’t done.

On March 13th of that year — just days after an attack — the man feared throughout the city sent a letter to the New Orleans Times-Picayune, the local newspaper. Well, purportedly, at least. We don’t know that the author of the letter was the actual axman, and never will. But whoever wrote the letter claimed to be the murderer, and even if only to be on the safe side, people took the note seriously.

The letter, in part, said the following:

Undoubtedly, you Orleanians think of me as a most horrible murderer, which I am, but I could be much worse if I wanted to. If I wished, I could pay a visit to your city every night. At will I could slay thousands of your best citizens (and the worst), for I am in close relationship with the Angel of Death.

Now, to be exact, at 12:15 (earthly time) on next Tuesday night, I am going to pass over New Orleans. In my infinite mercy, I am going to make a little proposition to you people. Here it is:

I am very fond of jazz music, and I swear by all the devils in the nether regions that every person shall be spared in whose home a jazz band is in full swing at the time I have just mentioned. If everyone has a jazz band going, well, then, so much the better for you people. One thing is certain and that is that some of your people who do not jazz it out on that specific Tuesday night (if there be any) will get the axe.

It’s that last part that the city of New Orleans took seriously — play jazz or risk falling prey to the ax. Throughout the city on that Tuesday night, the eclectic riffs of jazz music rang. Mental Floss summed it up eloquently: “Thousands of homes blasted jazz music loud enough to be heard by any passing murderers; those who didn’t own [radios or whatever] stuffed themselves into clubs and lounges or held block parties.” If you wanted to find a club playing something other than jazz that night, you couldn’t; no one wanted to invite death to their door.

The jazz-everywhere strategy worked — no one died at the hands of the axman that night. The killer did, however, strike a few more times that year, claiming another life in three separate attacks. After that, he disappeared without a trace. He was never caught.

Bonus fact: In the TV show “The Fresh Prince of Bel Air,” Will Smith’s best friend, “Jazz” (called DJ Jazzy Jeff on their albums, and Jeffrey Townes in real life) was the subject of a running gag. Jazz would do something obnoxious; Smith’s Uncle Phil would respond by physically throwing Jazz out of the house. (This happened a surprisingly-low 15 times over the course of the show’s 148-episode run, but that was often enough to make it recognizable.)

The only problem was that Jazz himself did the stunt — and he wasn’t much of a stuntman. He told HuffPo that he was pretty badly bruised by the time the director found a take he liked. Neither Jazz nor the rest of the production team wanted to shoot the throw for each of the 15 episodes — they wanted to use the same take for every throw. The solution? As Vice reported, if the script called for Jazz to be tossed aside, wardrobe would (almost always) put him in the same shirt.

Double bonus!: Ever wonder why the NBA has a team in Utah called the Jazz? It’s not because jazz music is popular in Salt Lake City. (Jazz music probably isn’t popular in Salt Lake City.) It’s because the Jazz are originally from New Orleans, but struggled financially there, and moved after five seasons.

From the Archives: Hangman’s Most Difficult Word: What’s this have to do with the above? You’ll see.