Why the National Animal of Scotland is… Wait, Really?

If nothing else, Wikipedia is a great place to find lists of things. For example, if you really need to find a list of recurring Star Trek: Deep Space Nine characters, Wikipedia has got you covered. We can get even more esoteric — how about a list of French-language Canadian game shows? Or a list of odd-toed ungulates by population? It’s a bit crazy.

But anyway, they also have normal lists, like this list of national animals. You’ll see a lot of expected or at least unsurprising entries; America’s bald eagle, India’s Bengal tiger and Indian elephant, Japan’s carp. All of those animals make sense — they’re fauna that you’ll find in the countries that claim them to be iconic. But the same can’t be said for the national animal of Scotland. You’ll never see one alive there — or anywhere else, for that matter. That’s because Scotland’s national animal is the unicorn. And while Scotland exists, unicorns, unfortunately, do not — and never have.

Of course, that wasn’t always well known. Go back 250 years ago and people commonly still thought unicorns were real — and for that matter, they were majestic, proud, and fearless. Those are all traits that one may want for a national animal, and perhaps that’s reason enough for Scotland to have chosen the unicorn. But one historian has discovered another likely explanation.

In the 1300s, Scotland didn’t like England all that much — the two countries shared an island but didn’t otherwise get along. England, in both 1296 and again in 1332, attempted to annex its neighbor by force, but in both cases, Scotland prevailed after decades of fighting. In 1390, when King Robert III of Scotland ascended to the throne, the fighting was over and Scotland was still an independent nation.

Robert III decided to drive that point home when he adopted his royal coat of arms. The English coat of arms at the time featured a lion, so it only made sense that the Scottish one would include whatever animal is the arch nemesis of a lion, right? Right. But what animal is that? Well, if you were born a few hundred years ago, chances are you’d say “unicorn.”

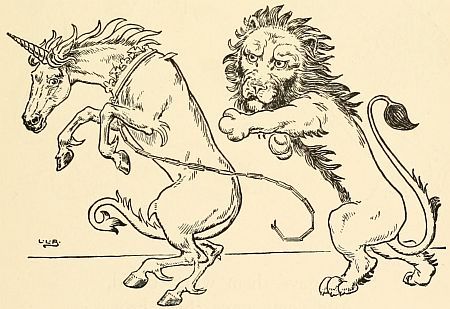

That’s according to historian Elyse Waters, who “first became interested in the subject,” according to the Scotsman, “when she discovered a medieval cookbook that included a recipe for how best to cook the mythical beasts.” Per Waters, the unicorn and the lion were considered enemies for millennia, even dating back to the ancient Babylonians more than 5,000 years ago. More contemporary treatises bear this out; a book from the 1600s titled “The History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents” (scans here, excerpted here) referred to the two as natural enemies while describing their strategies when encountering one another in battle. The image below also comes from that book, and you’ll see pretty clearly that the lion is attacking its nemesis.

Robert III saw England as Scotland’s mortal enemy; just as the unicorn was to the lion. And the unicorn had already made its way into Scottish lore — there are coins depicting the mythical animals dating back to the 1100s. As most of the world thought that unicorns were real — that error would continue commonly into the 1800s — adopting the beast as a national symbol was logical, despite the fact that there are no unicorns prancing around Scotland. When Robert III placed the unicorn in his coat of arms, he made it the national animal of Scotland — an honor it still holds today.

Ultimately, Scotland and England unified; first in 1603, when King James VI of Scotland also ascended to the English throne (as King James I of England and Ireland), and then officially under the Acts of Union in 1707. King James adopted a new coat of arms for general use, seen here, which incorporates both animals and a slightly different one (with the animals in opposite positions) in Scotland, seen here. Finally, the two mortal enemies came together, even if one never existed.

Bonus fact: Wikipedia really likes its lists. There are so many lists that it needs to have lists of those lists, just to make it easier to find the list you’re looking for. And, in an effort to be as complete as possible, its editors noticed that there were a lot of lists of lists — and that needed a list of its own. As a result, Wikipedia is home to a list of lists of lists. (There is not a “lists of lists of lists of lists”; however, people have tried to create it a few times.)

From the Archives: Stealing Back the Stone of Destiny: An English/Scottish squabble that was only resolved about 20 years ago.