Thanks for the Helium

If you wake up early enough on Thanksgiving Day and turn on the television, there’s a good chance you’ll find the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. Almost every year since 1924 — the festivities went on hiatus for three years during World War II — floats and balloons make their way down Manhattan’s West Side over the course of three hours. The parade has been televised nationally since 1952, and children across the country tune in to see their favorite cartoon characters depicted as enormous balloons kept afloat by massive amounts of helium.

But before the parade was televised, the balloons were a different sort of attraction — a lottery of sorts.

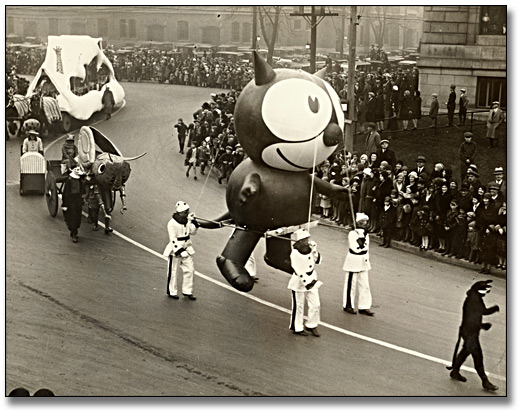

The first balloon featured Felix the Cat (above). It debuted in 1927, replacing live animals which had been part of the festivities for the three years prior. That year, Felix was filled with everyday air, not helium, and stood upright just off the ground — it didn’t float high above. It did, however, meet a premature end. According to Wikipedia, the balloon became tangled in wires, briefly caught fire, and was removed from the parade. Perhaps because of this balloon’s short window of viability, Macy’s didn’t really care too much about what happened to the balloons after the parade ended. So when helium-filled balloons entered the festivities a year later, Macy’s didn’t invest too much effort into figuring how to deflate them.

Instead, according to TIME, the balloons designed for the 1928 festivities — now helium-filled — were equipped with slow release valves. The valves would designed to keep the lighter-than-air gas inside the balloons for the duration of the parade with plenty of time to spare. But with no way (or perhaps, interest) in deflating the balloons quickly after the parade ended, Macy’s was left with a bunch of larger-than-life cartoon characters floating high above the street, tethered only by workers who were holding onto attached cables. The valves ensured that, at some point or another, the balloons would come down, and Macy’s wasn’t overly concerned about “when.” The instruction given to workers? Release the balloons into the afternoon sky.

While that seems like a terrible waste of what could be a pricey balloon or three, don’t worry — Macy’s had a recovery plan. At some point, hours or days or weeks later, the balloons would deflate, and hopefully do so above ground or somewhere salvageable by the people in that area. Each balloon came with return instructions, with a note offering the returning party $100 — that’s between $1,500 and $2,000 in today’s dollars, accounting for inflation — upon the safe return of the deflated balloon. Macy’s turned the parade’s end into the start of a high-reward, regional scavenger hunt.

Unfortunately, the plan didn’t work all too well. Of the five balloons launched in 1928, two landed in the water and a third one was torn to shreds by neighbors fighting over it (and the potential reward). Over the course of the next few years, only a handful of balloons were successfully returned, and some of those were riddled with bullet holes as bounty hunters tried to shoot the helium-filled characters down. And in 1932, a balloon ended up hitting a plane, causing the aircraft to enter into a tailspin.

That was the last time Macy’s released balloons into the skies above. Starting with the 1933 parade, the retail giant began deflating the balloons after use.

Bonus Fact: As noted above, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade has graced television sets since 1952. It debuted on NBC and has aired on that channel every year since. But if you tune into CBS on Thanksgiving morning, you’ll also be able to watch. Because the parade takes place outdoors and in public, Macy’s can’t prevent other news organizations from covering the event. They can, however, try to route around CBS’s cameras, which they’ve been actively trying to do in recent years — with limited success.

From the Archives: Balloonacy: Another reminder that what goes up, must come down.

Related: “Balloons of Broadway,” a book about the Macy’s parade balloons by someone who worked on them.