The Restaurant of Mistaken Orders

When you go to a restaurant and order yourself some food, you expect to get what you ordered. But, alas, sometimes that doesn’t happen. We’ve all been in a situation where something is just wrong — your salad comes with an ingredient you specifically asked to be omitted, the server forgets to bring that drink you wanted, or the hamburger you wanted comes as a cheeseburger. These are minor errors, sure, but they can be annoying. Most restaurants aren’t in the business of annoying their customers, so they try to avoid those types of mistakes.

But if you go to Toyko, you may find a restaurant where mistakes aren’t uncommon, or, for that matter, minor. But not only are those errors acceptable, they’re celebrated.

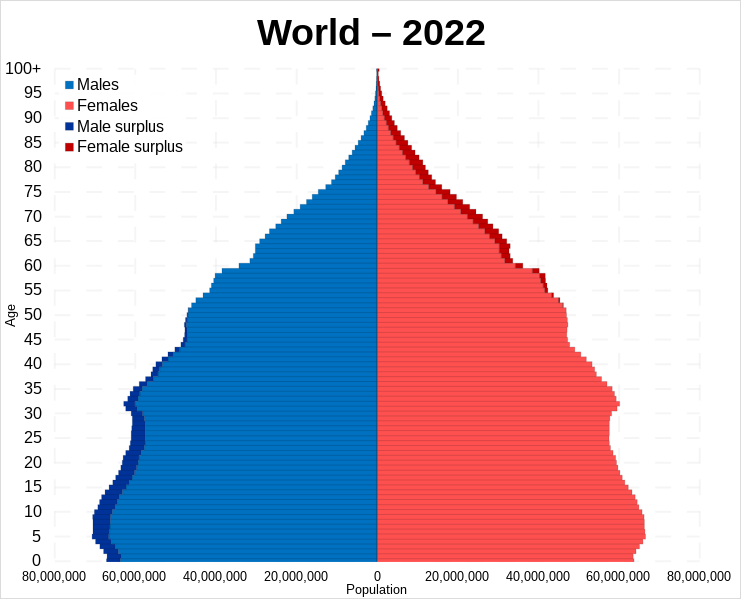

Why? Because of Japan’s demographics. Let’s start with a graph.

Pictured above is something called a “population pyramid.” it’s a way to visualize the age of a population, with each horizontal line representing (in the case above) everyone of a certain age. If you have a lot of babies being born, the bottom of the graph is the widest area, but as you go toward the top, the pyramid tends to narrow. This happens for two reasons: one, people die, leaving the graph before they reach advanced ages; and two, if you have a lot of people of child-bearing age, they can make a lot of new people, making the bottom of the graph even wider. The chart above, via Wikipedia, shows the world population in 2022, using UN data, and has that pyramidal shape you’d expect.

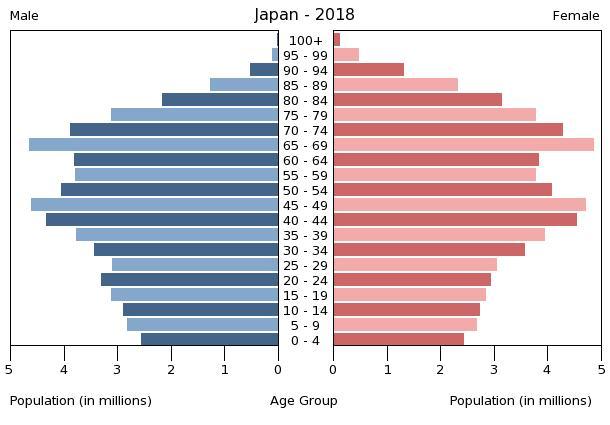

But Japan’s graph doesn’t look like that. Japan’s population, relative to most of the world, is old. Pictured below (again via Wikipedia, this time using data from the CIA World Factbook) is Japan’s population pyramid from 2018, and as you can see, it’s not much of a pyramid. In fact, the largest age cohort in the country is the 65-to-69-year-olds, and the number of octogenarians and up easily outpaces the number of newborns and toddlers.

Having an older population poses a lot of problems for Japanese society. For example, and of particular relevance for this story, is dementia. As the Japan Times reported in 2015, “one in five elderly people in Japan will have dementia in 2025,” with between 6.75 million and 7.3 million people suffering from the affliction by that time. And as anyone who is living with dementia or who has a loved one who is, the early stages of the condition can be humiliating — those afflicted are still able to do most of the things they’ve always done, but they tend to make unusual mistakes that can lead to embarrassment. It’s bad enough that the underlying disease may eventually them of their ability to care for themselves; the condition, though, as a way of robbing people of their dignity along the way.

In 2017, a restauranteur named Shiro Oguni decided to try to change that in a creative way: he decided to reduce the stigma around dementia-driven forgetfulness by embracing the mistakes. He created a 12-seat pop-up cafe known as the “Restaurant of Mistaken Orders,” where, according to a government press release, “the waiters and waitresses all have some degree of cognitive impairment.” Mistakes aren’t the goal — the servers are all trying to bring the right dish to the right customer — but as you’d expect (and as the name of the cafe makes clear), accidents happen. And that’s okay — it’s an opportunity for the diners to help, and everyone to build a better understanding for one another in a celebratory way. The government press release highlights one heartening story as an example:

One older woman shows her guests to a table and then sits down with them. Another serves a hot coffee with a straw. Yet another older woman struggles to twist a large pepper mill, not entirely sure that the pepper will fall where it’s wanted. Everybody at the table pitches in to help, and with cries of “We did it!” all join in the laughter. However, “The restaurant is not about whether orders are executed incorrectly or not,” notes Oguni. “The important thing is the interaction with people who have dementia.”

The restaurant does some things to help reduce the mistakes; for example, reports the Washington Post, “table numbers were difficult for the elderly to remember, so the staff switched them out for a centerpiece with a single flower, a different color for each table.” So you’re still more likely to get the dish you ordered than not — according to Tasting Table, “only 37% of orders at The Restaurant of Mistaken Orders are actually incorrect.” While that rate wouldn’t be acceptable at most restaurants, it’s still a reminder that people with dementia are still, quite often and with the right support, able to manage most of life’s questions — and that’s something Oguni and the Japanese government want to make clear. As Oguni writes on the restaurant’s website (per Tasting Table), “dementia is not what a person is, but just part of who they are,” and it’s incumbent on the rest of us to be okay with that — “the change will not come from them, it must come from society. By cultivating tolerance, almost anything can be solved.”

The Restaurant of Mistaken Orders is, according to its customers, doing a great job at moving the needle of tolerance in the right direction — because despite the mistakes, their customers couldn’t be happier. As NPR reported, even though 37% of the orders are delivered wrong, 99% of customers are happy,” per the restaurant.

Bonus fact: Japan is also trying to help its elderly population cope with dementia via QR codes. In 2016, a developer in the city of Iruma (about an hour from Toyko; here’s a map), per Bloomberg, “developed one-inch waterproof QR code stickers that can be affixed to a person’s fingernails or toenails. The stickers last about two weeks before deteriorating. The idea is that if a person is disoriented and lost, police can easily obtain their personal information, such as an address and telephone number, by scanning the sticker’s code.” The program won an award in 2022 for its innovative solution.

From the Archives: Dementiaville: Another neat idea — this one in the Netherlands — to help people with dementia live with dignity.