What’s So French About the F-Word?

In 1972, the late, great comedian George Carlin debuted a monologue titled “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television.” The seven words are also seven words you can’t say in this email newsletter (with a one-time exception, but you’ll have to do Google search for that one, sorry), so I won’t be listing them here. While Carlin’s title wasn’t quite accurate — those seven words weren’t specifically banned from TV broadcasts — the general rule is correct: one doesn’t use those seven words or a litany of others in polite company.

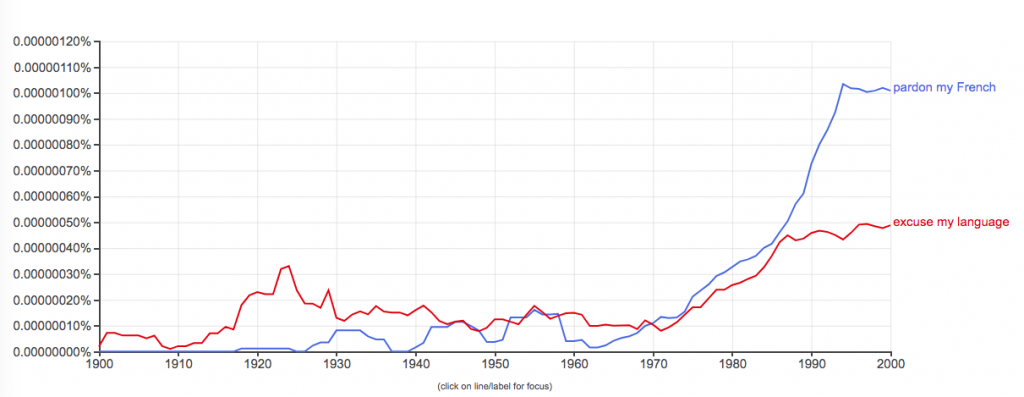

But if you do? You may want to apologize. And if you do, there’s a decent chance you might do say by saying “pardon my French.” Take a look at the graph below; it shows the language used in books from the last century or so. (It’s from Google’s Ngram Viewer, which you can play around with here.) Starting in the 1970s, “pardon my French” been an increasingly popular way to ask others to excuse your uncouth language. (Okay, it’s leveled off over the past few years, but close enough.)

But of the seven words — again, I’m not going to recite them — none of them are French. Neither are some of the more innocuous swear words like, uh, what “BS” stands for. So, where did the phrase come from?

It turns out, it’s because people were ashamed of being snobs.

The first modern use of “pardon my French” — actually, “excuse my French,” but the same idea — comes from an 1831 book titled “The Twelfth Night” by Baron Karl von Milte. Despite the author’s Germanic name, the book is almost entirely in English. The exception — well, the relevant exception — is the word “embonpoint” — a French word meaning “plump” or “overweight.” Specifically, one of the characters says the following:

Bless me, how fat you are grown!–absolutely as round as a ball:– you will soon be as embonpoint (excuse my French) as your poor dear father, the major.

It’s an odd phrase, right? The speaker says “excuse my French” literally, as “embonpoint” isn’t a curse word, it’s just a regular old French word. Further, while the speaker apologizes, he’s not apologizing for calling the other guy fat. He apologizes for using a French word to levy the insult. It’s a strange thing to apologize for — until you look into the history of it.

As Reader’s Digest notes, when William the Conqueror seized control of England, he installed a number of French-speaking Normans into leadership roles, and for generations afterward, much of the English nobility was bilingual, English and French. Language divided the elite from the commoners; the former would pepper French phrases into their speech but the latter could rarely understand the non-English words. And that caused division. As Mental Floss explains, “English speakers dropped French words or phrases into conversation—whether to display their culture, refinement or social class, or because sometimes only a French phrase has that certain je ne sais quoi—and then apologized for it if the listener wasn’t familiar with the word or didn’t speak the language.” In effect, the speaker was offering an empty apology for using language which was impolite.

Over time, that more general use — “sorry for using language inappropriate for the social setting, even though I’m not really sorry” — broadened to include swear words. And as it became increasingly okay to use foreign phrases in everyday language, the original reason to apologize for using French words in English speech dissipated.

No matter how you cut it, though, there’s nothing actually French about the F-word or Carlin’s six other favorites.

Bonus fact: When Carlin first performed his “Seven Words” monologue, there were no laws a no major court rulings which specifically barred the use of those words, but TV networks self-censored and rarely, if ever, broadcast similar profanity. Carlin, however, changed that — and not in his favor. In 1973, WBAI, a New York-based FM radio station, aired part of Carlin’s routine, prompting complaints to the FCC. The FCC reprimanded the station but its owners sued, claiming that the First Amendment gave the station carte blanche (pardon my French) to broadcast whatever, whenever. By a 5-4 vote, the Supreme Court disagreed.

From the Archives: Thomas the Tank Engine’s Unlikely Friend: The famous train is not related to the above… or is it?