Why You Couldn’t Watch the First Super Bowl

Last night, the New England Patriots and Los Angeles Rams faced off in Super Bowl LIII — that’s 53, for those who don’t speak Roman numerals. If you didn’t watch the game and don’t know who won, well, you can find that anywhere — it is a huge media event and video of the game is virtually everywhere. And not just highlights, either. Ultimately, the full game will be made available for your re-watching pleasure, be it on DVD or some sort of streaming service. That’s true about last night’s game and it’s true about every Super Bowl since the first.

But the first Super Bowl itself? That one — well, it’s complicated.

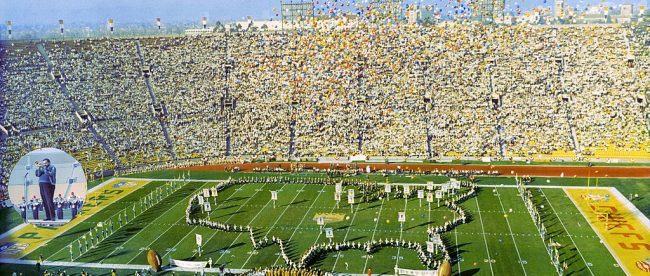

Super Bowl I took place on January 15, 1967, in Los Angeles, California, with the Green Bay Packers beating the Kansas City Chiefs by a score of 35-10. Dubbed the “AFL-NFL World Championship Game” at the time, it holds the distinction of being the only Super Bowl to be aired, simultaneously, on two different TV networks in the United States. At the time, CBS had the rights to broadcast NFL games while NBC had the same for AFL games. Unable to resolve this duality, both broadcasters aired the game live that evening.

But the historic nature of what was on their airways was not clear at the time — it wasn’t even formally called the “Super Bowl.” After broadcasting the game, both CBS and NBC, in cost-cutting efforts, erased their recordings of the games in order to get clean tapes for other programs. While, as Wikipedia notes, that was “a common practice in the TV industry at the time,” in retrospect, that was pretty silly. The VCR wasn’t yet invented — that was almost a decade away — making it unlikely that anyone else had a recording of the game. Video of the first Super Bowl seemed to be lost to history.

That changed in 2005 — kind of. That year, Sports Illustrated ran an article titled “SI”s 25 Lost Treasures,” a list of items in sports history which, as the title suggests, were potentially gone forever. Among the list was a recording of Super Bowl I, which the magazine estimated could be worth “more than $1 million.” And one of the people who read that article was a guy named Clint Hepner. Hepner, as a kid, was friends with someone named Troy Haupt, and Hepner vaguely remembered that Troy’s mom had a copy of the game, somehow, in the attic. Hepner suggested to Haupt that the latter look into it, and it turned out, Hepner was right. The New York Times continues:

Haupt’s father, Martin, taped the game. Haupt never knew him. Haupt and his mother, Beth Rebuck, say they have no idea what he did for a living back then. They also don’t know why he went to work on Jan. 15, 1967, with a pair of two-inch Scotch tapes, slipped one, and then the other, into a Quadruplex taping machine and recorded the Green Bay Packers’ 35-10 win over the Kansas City Chiefs. He told his family nothing about his day’s activity.

The couple divorced at some point over the next few years and, in 1975, Martin — dying from cancer — told his ex about the tapes for the first time. But Beth didn’t think much of it, and the tapes gathered dust for years until the younger Haupt, spurred by his friend, went digging among the rest of his father’s forgotten stuff. And what he found was like winning the lottery, at least if that Sports Illustrated estimate was accurate.

It wasn’t.

In or around 2011, Haupt offered the tapes to the NFL for $1 million, likely using the SI article as a basis for the amount requested. The league reportedly counter-offered $30,000. Both sides refused to budge, putting the parties at an impasse. But the NFL wasn’t done. The league argued that the elder Haupt’s tapes violated their copyright and, therefore, Troy couldn’t sell the tapes to anyone without their permission. The only known copy of Super Bowl I sat on a shelf, unwatched by the millions of fans who could be interested in such a thing.

Ultimately, the NFL made it moot. As Gizmodo explained, “for the next five years, the league’s lawyers successfully kept Troy Haupt, who discovered the tapes, from releasing more than a few seconds of the footage to the media. Then, in 2016, three weeks before the kickoff of Super Bowl 50, the NFL suddenly released its own version of the game, which it had cobbled together from extant film reels and audio taken from an NBC radio broadcast.” A condensed version of the game is now available on the NFL’s YouTube channel, here, and per various reports, Haupt still hasn’t been able to sell his copy.

Bonus fact: When an NFL game fails to sell out all its tickets, league rules prevent the local broadcaster from airing the game — historically, the league doesn’t want TV viewership cannibalizing ticket sales. And if you lived in Los Angeles during Super Bowl I, you were caught in that snare, as Super Bowl I has the dubious distinction of being the only Super Bowl to not be a sell-out. The Los Angeles Coliseum, at the time, had the capacity for more than 90,000 fans; only about two-thirds were actually sold. The likely reason: ticket prices. At $12 (about $90 in today’s dollars), that seems like a bargain. But not so much to the press at the time. According to Wikipedia, “local newspapers printed editorials about what they viewed as a then-exorbitant $12 price for tickets,” instead explaining to fans how to watch the game on TV, despite local blackouts, by tuning into nearby CBS and NBC affiliates.

From the Archives: The Super Bowl Commercial Designed To Be Missed: High life.