Saved by the Bell

George Washington, the first President of the United States, died on December 14, 1799. He was interred four days later at his plantation home in Virginia, Mount Vernon. While some would (had they been alive to notice) object to such a delay, Washington probably did not mind. Yes, the delay was mostly so that the recently deceased American forefather could be properly honored. But according to legend, Washington’s deathbed request was that he be buried no sooner than two days after he was pronounced dead. Why? Because apparently, George Washington feared being buried alive.

Such fears were, sadly, not unfounded. In the 13th century, a highly regarded philosopher/theologian, John Duns Scotus, was rumored to have been buried alive; as the story goes, his body was found next to his coffin, arms and hands bloodied from an attempt to claw his way out. (The story is probably a myth.) A book on the subject (titled “Buried Alive,” even) tells the tale of London butcher named Lawrence Cawthorn, who, in the 1660s, fell ill and was “hastily buried” by his “wicked landlady.” When mourners visited his gravesite, they heard “a muffled shriek from the tomb and [. . ..] frenzied clawing at the coffin walls.” By the time Cawthorn was disinterred, he was dead. And according to another book on the subject (“The Corpse: A History“) in 1905, British businessman William Tebb (best known as an anti-vaccination activist), cobbled together over 300 cases of live burials and near misses.

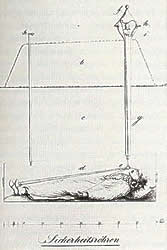

To combat these fears, coffin makers came up with a solution: the “safety coffin.” Popular in the late 1700s and into the subsequent century, the safety coffin typically involved some sort of way for the accidentally buried to to notify those above him or her about the mistake. One example (schematic seen above) involved a long tube and cord running many feet (more than six!) upward from the coffin. At the top was a bell, such that a wrongfully-interred person could shake the cord, ring the bell, and ideally, have others come with shovels to save him from a horrible end to his existence. Other methods included pyrotechnics, flags, and even escape hatches. An early one involved a lock with a keyhole inside the coffin; the body was to be buried wearing a coat with the key placed within an inside pocket. There is actually a lot of innovation around the problem — and a similarly large number of patents.

Were these safety coffins successful? Probably not — there are no known examples of a safety coffin rescuing a buried-alive person. There are, however, a few examples of false positives. If, when interred, the body was holding the cord, natural decomposition could cause the cord to tense up and, therefore, ring the bell. To prevent “small” movements from causing these false alarms, in 1897, one Russian inventor created a system which detected more significant movements and signalled that someone was alive to outsiders. The only problem? When he demonstrated it by “burying” one of his assistants, alive, the motion detection system failed. The assistant emerged unharmed but the safety coffin failed to find many buyers.

Bonus fact: George Washington was interred at Mount Vernon, where his tomb remains today. But if the United States Congress had its way, he would have been buried in the Capitol. As Wikipedia notes, in December of 1800, a year after President Washington died, the House of Representatives appropriated $20,000 ($2.6 million in today’s dollars) for a marble pyramid with a 100 square foot base to act as a mausoleum for him. But the plan failed to go further when Southern states objected, requesting that Washington’s body remain in Virginia.

From the Archives: Die Hard: If anyone was likely to be buried alive, it was this guy — who was incredibly hard to murder.

Related: The Relaxman Relaxation Capsule: Kind of like a coffin, only (a) not for dead people, (b) not intended for burial, (c) probably more comfortable, and (d) $50,000.

Leave a comment